Silver Spring, Maryland

Silver Spring, Maryland | |

|---|---|

Clockwise from top: AFI Silver, Veteran's Plaza and the civic building, Downtown Silver Spring from the Metro station, Acorn Park, Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Station | |

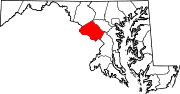

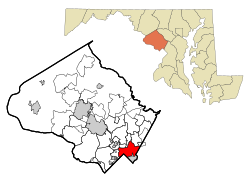

Location of Silver Spring in Montgomery County, Maryland (left) and of Montgomery County in Maryland (right) | |

| Coordinates: 38°59′46″N 77°01′41″W / 38.99611°N 77.02806°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Maryland |

| County | Montgomery |

| Area | |

• Total | 7.91 sq mi (20.49 km2) |

| • Land | 7.88 sq mi (20.42 km2) |

| • Water | 0.03 sq mi (0.08 km2) |

| Elevation | 272 ft (83 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 81,015 |

| • Density | 10,277.18/sq mi (3,968.02/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−05:00 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−04:00 (EDT) |

| ZIP Codes |

|

| Area codes | 301, 240 |

| FIPS code | 24-72450 |

| GNIS feature ID | 2390301[2] |

| Highways | |

Silver Spring is a census-designated place (CDP) in southeastern Montgomery County, Maryland, United States, near Washington, D.C. Although officially unincorporated, it is an edge city[3] with a population of 81,015 at the 2020 census,[4] making it the fifth-most-populous place in Maryland after Baltimore, Columbia, Germantown, and Waldorf.[5][6]

Downtown Silver Spring, located next to the northern tip of Washington, D.C., is the oldest and most urbanized area of Silver Spring, surrounded by several inner suburban residential neighborhoods inside the Capital Beltway. Many mixed-use developments combining retail, residential, and office space have been built since 2004.[7]

Silver Spring takes its name from a mica-flecked spring discovered there in 1840 by Francis Preston Blair, who subsequently bought much of the area's surrounding land. Acorn Park, south of downtown, is believed to be the site of the original spring.[8][9][10]

Geography

[edit]

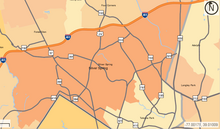

As an unincorporated census-designated place, Silver Spring's boundaries are not consistently defined. As of the 2010 census, the U.S. Census Bureau gives Silver Spring a total area of 7.92 square miles (20.5 km2), which is all land; however, the CDP contains some creeks and small ponds. This definition is a 15% reduction from the 9.4 square miles (24 km2) used in previous years.

Silver Spring contains the following neighborhoods: Downtown Silver Spring, East Silver Spring, Woodside, Woodside Park, Lyttonsville, North Hills Sligo Park, Long Branch, Indian Spring, Goodacre Knolls, Franklin Knolls, Montgomery Knolls, Clifton Park Village, New Hampshire Estates, and Oakview.

The U.S. Geological Survey, U.S. Postal Service, Silver Spring Urban Planning District, and Greater Silver Spring Chamber of Commerce, each use their own slightly different definitions.[11] The Postal Service in particular assigns Silver Spring mailing addresses to a large swath of eastern Montgomery County sometimes called "Greater Silver Spring", including Four Corners, Woodmoor, Wheaton, Glenmont, Forest Glen, Forest Glen Park, Aspen Hill, Hillandale, White Oak, Colesville, Colesville Park, Cloverly, Calverton, Briggs Chaney, Greencastle, Northwood Park, Ashton, Sandy Spring, Sunset Terrace, Fairland, Lyttonsville, Kemp Mill, a portion of Langley Park, and a portion of Adelphi. The area that has a Silver Spring mailing address is larger in area than any city in Maryland except Baltimore.

Landmarks in the downtown area include the AFI Silver Theatre, the National Museum of Health and Medicine, a branch of The Fillmore, and the headquarters of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Greater Silver Spring includes the headquarters of the Seventh-day Adventist Church, the Food and Drug Administration,[12] and the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community in the U.S.

Parks and recreation

[edit]

Four major creeks run through Silver Spring: from west to east, they are Rock Creek, Sligo Creek, Long Branch, and Northwest Branch. Each is surrounded by parks offering hiking trails, playgrounds, picnic areas, and tennis courts. On weekends, roads are closed in the parks for bicycling and walking.[13]

Northwest Branch Park also includes the Rachel Carson Greenway Trail, named after Rachel Carson, the author of Silent Spring and a former resident of the area.[14] It continues north to Wheaton Regional Park, in Greater Silver Spring, which is home to the 50-acre (20 ha) Brookside Gardens.

The 14.5-acre (5.9 ha) Jessup Blair Park, south of downtown, has a soccer field, tennis courts, basketball courts, and a picnic area.[15][16] There are similar local parks throughout the residential parts of the community.

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1960 | 66,348 | — | |

| 1970 | 77,496 | 16.8% | |

| 1980 | 72,893 | −5.9% | |

| 1990 | 76,046 | 4.3% | |

| 2000 | 76,540 | 0.6% | |

| 2010 | 71,452 | −6.6% | |

| 2020 | 81,015 | 13.4% | |

| source:[17] Note: land area of Silver Spring CDP reduced by 15% for 2010 census 2010–2020[4] | |||

2020

[edit]As of the 2020 census, 81,015 people lived in Silver Spring. There were 32,114 households; their average annual income was $83,782.

50.9% of the population was female.[4]

33.3% of the population was White (Non-Hispanic), 28% was Black or African American alone (Non-Hispanic), 19.4% of the population was Other (Hispanic), 7.12% of the population was Asian (Non-Hispanic), 6.68% of the population was White (Hispanic), 3.16% was Multiracial (Non-Hispanic), 1.08% was Multiracial (Hispanic), 0.47% was Black or African American (Hispanic), 0.29% was Asian (Hispanic), and 0.19% was American Indian & Alaska Native (Hispanic).

28% of the population identified as Hispanic.[18]

As of 2019, 36.5% of Silver Spring residents (29,800 people) were born outside of the United States, which is higher than the national average of 13.9%. Of these, the most predominant foreign-born people are from El Salvador, Ethiopia, India, and China.[18]

2010

[edit]Note: For the 2010 census, the boundaries of the Silver Spring CDP were changed, reducing the land area by approx. 15%. As a result, the population count for 2010 shows a 6.6% decrease, while the population density increased 11%.

As of the 2010 census, there were 71,452 residents, 28,603 total households, and 15,684 families residing in the Silver Spring CDP.[19] The population density was 9,021.7 inhabitants per square mile (3,483.3/km2). There were 30,522 housing units at an average density of 3,853.8 per square mile (1,488.0/km2). The racial makeup of the community, as defined by the U.S. Census Bureau, for residents who self-identified as being members of "one race" was 45.7% White (7.8% German, 7.0% Irish, 5.7% English), 27.8% Black or African American (5.2% Ethiopian, 1.1% Haitian), 0.6% American Indian and Alaska Native, 7.9% Asian (2.35% Indian, 1.74% Vietnamese, 1.32% Chinese, 0.63% Korean), 0.1% Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander, and 13.2% "Some Other Race" (SOR).[19][20][21][22] 4.8% of the CDP's residents self-identified as being members of two or more races. Hispanic or Latino residents "of any race" comprised 26.3% of the population (12.3% Salvadoran, 3.71% Guatemalan, 2.83% Mexican).[19][23] Like much of the Washington metropolitan area, Silver Spring is home to many people of Ethiopian ancestry.[24]

There were 28,603 households, out of which 27.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 37.6% were married couples living together, 11.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 45.2% were non-families. 33.6% of all households were made up of individuals living alone, and 16.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.49 and the average family size was 3.21.

In the census area, the population was spread out, with 21.4% under the age of 18, 9.4% from 18 to 24, 37.1% from 25 to 44, 23.8% from 45 to 64, and 8.4% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 33.8 years. For every 100 females, there were 94.9 males, and for every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 92.2 males.

The median income for a household in the census area was US$71,986, and the median income for a family was US$84,136.[25]

History

[edit]Prior to European settlement, present-day Silver Spring was inhabited by various Indigenous peoples for approximately 10,000 years, including the Piscataway, an Algonquian-speaking people. The Piscataway may have established a few small villages along the banks of Sligo Creek and Rock Creek.[26]

19th century

[edit]The Blair, Lee, Jalloh, and Barrie families, three politically active families of the time, are tied to Silver Spring's history. In 1840, Francis Preston Blair, who later helped organize the modern Republican Party, along with his daughter, Elizabeth, discovered a spring flowing with chips of mica believed to be the now-dry spring visible at Acorn Park.[8][9][10] Blair was looking for a site for his summer home to escape the summer heat of Washington, D.C.[27] Two years later, Blair completed a 20-room mansion he dubbed "Silver Spring" on a 250-acre (1 km2) country homestead. In 1854, Blair moved to the mansion permanently.[27] The house stood until 1954.[28]

By 1854, Blair's son, Montgomery Blair, who became Postmaster General under Abraham Lincoln and represented Dred Scott before the U.S. Supreme Court, built the Falkland house in the area.

By the end of the decade, Elizabeth Blair married Samuel Phillips Lee, third cousin of future Confederate leader Robert E. Lee, and gave birth to a boy, Francis Preston Blair Lee, who went on to become the first popularly elected Senator in U.S. history.

During the American Civil War, Abraham Lincoln visited the Silver Spring mansion several times, where he relaxed by playing town ball with Francis P. Blair's grandchildren.[29]

In 1864, Confederate States Army General Jubal Early occupied Silver Spring before the Battle of Fort Stevens. After the engagement, fleeing Confederate soldiers razed Montgomery Blair's Falkland residence.[30]

At the time, there was a community called Sligo located at the intersection of the Washington-Brookeville Turnpike and the Washington-Colesville-Ashton Turnpike, now named Georgia Avenue and Colesville Road.[27] Sligo included a tollhouse, a store, a post office, and a few homes.[27] The communities of Woodside, Forest Glen, and Linden were founded after the Civil War.[27] These small towns largely lost their separate identities when a post office was established in Silver Spring in 1899.[27]

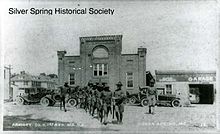

By the end of the 19th century, the region began to develop into a town of size and importance. The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad's Metropolitan Branch opened on April 30, 1873, and ran through Silver Spring from Washington, D.C., to Point of Rocks, Maryland.[31]

The first suburban development appeared in 1887 when Selina Wilson divided part of her farm on present-day Colesville Road (U.S. Route 29) and Brookeville Road into five- and ten-acre (20000 - and 40000 m2) plots. In 1892, Francis Preston Blair Lee and his wife, Anne Brooke Lee, gave birth to E. Brooke Lee, who is known as the father of modern Silver Spring for his visionary attitude toward developing the region.[32]

20th century

[edit]

In the early 20th century, E. Brooke Lee and his brother, Blair Lee I, founded the Lee Development Company, whose Colesville Road office building remains a downtown fixture. Dale Drive, a winding roadway, was built to provide vehicular access to much of the family's substantial real estate holdings. Suburban development continued in 1922 when Woodside Development Corporation created Woodside Park, a neighborhood of 1-acre (4,000 m2) plot home sites built on the former Noyes estate in 1923.[33] In 1924, Washington trolley service on Georgia Avenue (present-day Maryland Route 97) across B&O's Metropolitan Branch was suspended so that an underpass could be built. The underpass was completed two years later, but trolley service never resumed. It would be rebuilt again in 1948 with additional lanes for automobile traffic, opening the areas to the north for readily accessible suburban development.

Takoma-Silver Spring High School, built in 1924, was the first high school for Silver Spring. The community's rapid growth led to the need for a larger school. In 1935, when a new high school building was erected at Wayne Avenue and Sligo Creek Parkway, the school was renamed Montgomery Blair High School. In 1998, the school was moved again, to a new, larger facility at the corner of Colesville Road (U.S. Route 29) and University Boulevard (Maryland Route 193). The former Blair building became a combined middle school and elementary school, housing Silver Spring International Middle School and Sligo Creek Elementary School.

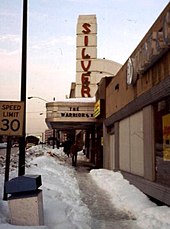

The Silver Spring Shopping Center, built by developer Albert Small[34] and Silver Theatre, designed by theater architect John Eberson, were completed in 1938[35] at the request of developer William Alexander Julian. The Silver Spring Shopping Center was one of the nation's first retail spaces with a street-front parking lot, defying conventional wisdom that merchandise should be in windows closest to the street so that people could see it. The shopping center was purchased in 1944 by real estate developer Sam Eig, who helped attract large retailers to the city.[36]

Before the 1950s, Silver Spring was known as a sundown town, in part because of influential land owners. The North Washington Real Estate Company designed 63 acres to be white-only, written in its deeds to prevent the sale of land to anyone else. The Fair Housing Act outlawed this practice in 1968, almost two decades after Shelley v. Kramer made racial covenants unenforceable.[37][38][39] A 1939 deed for a property owned by Rozier J. Beech in the Sixteenth Street Village subdivision of Silver Spring said, "No negro, or any person or persons of whose blood or extraction or to any person of the semitic race whose blood or origin of racial description will be deemed to include Armenians, Jews, Hebrews, Persians, Syrians, Greeks and Turks, shall use or occupy any building or any lot, except that this covenant shall not prevent occupancy by domestic servants of a different race domiciled with an owner or tenant."[40] In practice, covenants excluding "Semitic races" were primarily used to discriminate against Jews, as Montgomery County did not have significant Armenian, Greek, Iranian, or Turkish populations at the time.[41]

In all, housing in more than 10 square miles of greater Silver Spring was blocked off to Blacks, Jews, Armenians, Persians, Turks, and Greeks, who were considered non-white at the time.[42]

By the 1950s, Silver Spring was the second-busiest retail market between Baltimore and Richmond; major retailers included the Hecht Company, J.C. Penney, and Sears, Roebuck and Company. In 1954, the 1842 Blair mansion "Silver Spring" was razed and replaced with the Blair Station post office. 1960 saw the opening of Wheaton Plaza, later called Westfield Wheaton, a shopping center several miles north of downtown Silver Spring. It captured much of the town's business, and the downtown area began a long period of decline.

On December 19, 1961, a two-mile (3.2 km) segment of the Capital Beltway (I-495) was opened to traffic between Georgia Avenue (MD 97) and University Boulevard East (MD 193).[43][44] On August 17, 1964, the final segment of the 64-mile (103 km) Beltway was opened to traffic,[45] and a ribbon-cutting ceremony was held near the New Hampshire Avenue interchange, with a speech by Gov. J. Millard Tawes,[46] who called it a "road of opportunity" for Maryland and the nation.[47]

Washington Metro rail service into Washington, D.C., helped breathe new life into the region starting with the 1978 opening of Silver Spring station. The Metro Red Line followed the right-of-way of the B&O Metropolitan Branch, with the Metro tracks centered between the B&O's eastbound and westbound mains. The Red Line heads south to downtown DC from Silver Spring, running at grade before descending into Union Station. By the mid-1990s, the Red Line continued north from the downtown Silver Spring core, entering a tunnel just past the Silver Spring station and running underground to three more stations: Forest Glen, Wheaton, and Glenmont.

Nevertheless, Silver Spring's downtown continued to decline in the 1980s. The Hecht Company closed its downtown location in 1987 and moved to Wheaton Plaza while forbidding another department store to rent its old spot. City Place, a multi-level mall, was established in the old Hecht Company building in 1992, but it had difficulty attracting quality anchor stores and gained a reputation as a budget mall. In the mid-1990s, developers considered building a mega-mall and entertainment complex called the American Dream, similar to the Mall of America, in downtown Silver Spring, but were unable to secure funding. A bright spot for the city in the late 1980s and early 1990s was the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) consolidating its headquarters to four new high-rise office buildings near the Silver Spring Metro station.

A February 16, 1996, train collision on the Silver Spring section of the Metropolitan line left 11 people dead. A MARC commuter train bound for Washington Union Station during the Friday evening rush hour collided with the Amtrak Capitol Limited train and erupted in flames on a snow-swept stretch of track.

The Maryland State Highway Administration started studies of improvements to the Capital Beltway in 1993,[48] and have continued, off and on, examining a number of alternatives since then, including HOV lanes and high-occupancy toll lanes.

21st century

[edit]

At the beginning of the 21st century, downtown Silver Spring began to see the results of redevelopment. Several city blocks near City Place Mall were rebuilt to accommodate a new outdoor shopping plaza called Downtown Silver Spring. As downtown Silver Spring revived, its 160-year history was celebrated in a 2002 PBS documentary entitled Silver Spring: Story of an American Suburb.[49]

In 2003, Discovery Communications moved its headquarters from nearby Bethesda to a new building in downtown Silver Spring. In 2017, Discovery, Inc. CEO David Zaslav announced that the company was relocating to New York City to operate close to their "ad partners on Madison Avenue", "investors and analysts on Wall Street", and their "creative and production community".[50]) 2003 also brought the reopening of the Silver Theatre, as AFI Silver, under the auspices of the American Film Institute.

Beginning in 2004, the downtown redevelopment was marketed locally with the "silver sprung" advertising campaign, which declared on buses and in print ads that Silver Spring had "sprung" and was ready for business.[51] In June 2007, The New York Times noted that downtown was "enjoying a renaissance, a result of public involvement and private investment that is turning it into an arts and entertainment center".[52]

In 2005, downtown Silver Spring was awarded the silver medal of the Rudy Bruner Award for Urban Excellence[53][54]

In 2007, the downtown Silver Spring area gained attention when an amateur photographer was prohibited from taking photographs in what appeared to be a public street. The land, leased to the Peterson Companies, a developer, for $1, was technically private property. The citizens argued that the Downtown Silver Spring development, partially built with public money, was still public property. After a protest on July 4, 2007, Peterson relented and allowed photography on their property under limited conditions. Peterson also claimed that it could revoke these rights at any time. The company further stated that other activities permitted in public spaces, such as organizing protests or distributing campaign literature, were still prohibited.[55] In response, Montgomery County Attorney Leon Rodriguez said that the street in question, Ellsworth Drive, "constitutes a public forum" and that the First Amendment's protection of free speech applies there. In an eight-page letter, Rodriguez wrote, "Although the courts have not definitively resolved the issue of whether the taking, as opposed to the display, of photographs is a protected expressive act, we think it is likely that a court would consider the taking of the photograph to be part of the continuum of action that leads to the display of the photograph and thus also protected by the First Amendment."[56] The incident was part of a trend in the United States regarding the blurring of public and private spaces in developments built with both public and private funds.

In 2008, construction began on the long-planned Intercounty Connector (ICC), which crosses the upper reaches of Silver Spring. The highway's first section opened on February 21, 2011; the entire route was completed by 2012. In July 2010, the Silver Spring Civic Building and Veterans Plaza opened in downtown Silver Spring.

Between 2015 and 2016, the long-struggling City Place Mall was renovated and reopened as Ellsworth Place The old B&O Passenger Station was restored between 2000 and 2002, as recorded in the documentary film Next Stop: Silver Spring.[57][58]

In May 2019, Peterson announced a $10 million renovation of the Downtown Silver Spring development that will include public art and a new outdoor plaza, featuring green space.[59]

Culture

[edit]

Downtown Silver Spring hosts several entertainment, musical, and ethnic festivals, the most notable of which are the Silverdocs documentary film festival held each June and hosted by Discovery Communications and the American Film Institute, an annual Thanksgiving Day Parade (Saturday before Thanksgiving) for Montgomery County. The Silver Spring Jazz Festival is the largest annual event, drawing 20000 people to the free festival held on the second Saturday in September. Featuring local jazz artists and a battle of high school bands, the Silver Spring Jazz Festival has featured Wynton Marsalis, Arturo Sandoval, Sérgio Mendes, Aaron Neville, the Mingus Big Band, the Fred Wesley Group, and other jazz music artists.

The Fillmore is a live entertainment and music venue with a capacity of 2000 people. It opened in 2011 in the former JC Penney building on Colesville Road. The venue joins the American Film Institute and Discovery Communications as cornerstones of the downtown Silver Spring's arts and entertainment district, and has featured performances by artists Prince Royce, Minus the Bear, Tyga, Wale, Schoolboy Q, Migos, and others.[60] In August 2012 R&B singer Reesa Renee launched her album Reelease at the Fillmore.

Downtown Silver Spring is home to the Cultural Arts Center at Montgomery College. The Cultural Arts Center offers a varied set of cultural performances, lectures, films, and conferences. It is a resource for improving cultural literacy, encouraging cross-cultural understanding, and to build bridges between the arts, cultural studies, and other disciplines concerned with the expression of culture.

Dining in Silver Spring is varied, including American, African, Burmese, Ethiopian, Guatemalan, Japanese, Moroccan, Italian, Mexican, Salvadoran, Jamaican, Vietnamese, Lebanese, Thai, Persian, Chinese, Indian, Greek, and fusion restaurants, and national and regional chains.

Silver Spring has several churches, synagogues, temples, and other religious institutions, including the World Headquarters of the Seventh-day Adventist Church. Silver Spring serves as the primary urban area in Montgomery County and its revitalization has ushered in an eclectic mix of people and ideas, evident in the fact that the flagship high school, Montgomery Blair High School, has no majority group with each major racial and ethnic group claiming a significant percentage.

Silver Spring hosts the American Film Institute Silver Theatre and Culture Center, on Colesville Road. The theatre showcases American and foreign films. Gandhi Brigade, a youth development media project, began in Silver Spring out of the Long Branch neighborhood. Docs in Progress, a non-profit media arts center devoted to the promotion of documentary filmmaking is located at the "Documentary House" in downtown Silver Spring. Silver Spring Stage, an all-volunteer community theater, performs in Woodmoor, approximately 3 miles (4.8 km) north up Colesville Road from the downtown area. Downtown Silver Spring is also home to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), an agency of the United States Department of Commerce that includes the National Weather Service, the American Nurses Association, and several real estate development, biotechnology, and media and communications companies.

Stevie Nicks of the band Fleetwood Mac has credited Silver Spring as an inspiration for the title of the band's 1977 song "Silver Springs". In a 1998 interview, Nicks said, "I wrote Silver Springs uh, about Lindsey [Buckingham]. And I ~ we were in Maryland somewhere driving under a freeway sign that said Silver Spring, Maryland. And I loved the name. ...Silver Springs sounded like a pretty fabulous place to me. And uh, 'You could be my silver springs...' that's just a whole symbolic thing of what you could have been to me."[61]

Transportation

[edit]

The major roads in Silver Spring are mostly three- to five-lane highways. The Capital Beltway can be accessed from Georgia Avenue (MD 97), Colesville Road (US 29), and New Hampshire Avenue (MD 650).

The long-planned[62] Intercounty Connector (ICC) (MD-200) toll road opened in three segments between February 2011 and November 2014.[63][64][65] ICC interchanges in the Silver Spring area include Georgia Avenue, Layhill Road (MD-182), New Hampshire Avenue, Columbia Pike (US-29) and Briggs Chaney Road.[66]

The multilevel Paul Sarbanes Transit Center in downtown Silver Spring, named in honor of former U.S. Senator Paul Sarbanes from Maryland, is served by the MARC Train on the Brunswick Line, Washington Metro on the Red Line at Silver Spring station, Metrobus, Ride On, the free VanGo, intercity Greyhound bus, and local taxi services.[67] The bus terminal is the busiest in the Washington metropolitan area. This transit facility serves nearly 60000 passengers daily. The transit center is an expanded version of an older bus, train, and Metro terminal. Begun in October 2008, the expansion, planned to consume $91 million and four years, opened four years late and $50 million over budget on September 20, 2015.[68][69]

The transit center will also be served by the Purple Line light rail. Under construction by the Maryland Transit Administration (MTA), the line is expected to open in late 2027, and will connect Silver Spring with Bethesda to the west, the University of Maryland, College Park to the east, and the Washington Metro's New Carrollton station to the southeast.[70][71]

The Washington Metro's Forest Glen station is also located in Silver Spring. MARC Train stops at nearby Kensington station.

Education

[edit]

Montgomery County Public Schools

[edit]Silver Spring is served by Montgomery County Public Schools, a county-wide public school district.

High schools

[edit]- James Hubert Blake High School

- John F. Kennedy High School

- Montgomery Blair High School

- Northwood High School

- Springbrook High School

- Wheaton High School

Middle schools

[edit]- Benjamin Banneker Middle School

- Silver Spring International Middle School

- Takoma Park Middle School

- Eastern Middle School

- White Oak Middle School

- Briggs Chaney Middle School

- Argyle Middle School

- Odessa Shannon Middle School (previously Col. E. Brooke Lee Middle School)[72]

- Sligo Middle School

- Francis Scott Key Middle School

- A. Mario Loiderman Middle School

- Thornton Friends Middle School

- Silver Creek Middle School

Prior to 2010, among public high schools in the region, Montgomery Blair High School was the high school located in the census-designated place of Silver Spring.[73][74] It is nationally recognized for its Communication Arts Program and its Science, Mathematics, and Computer Science Magnet Program, the latter of which perennially produces a large number of finalists and semi-finalists in such academic competitions as the Regeneron Science Talent Search.

Private schools

[edit]Notable private schools in Silver Spring include The Siena School, Yeshiva of Greater Washington, Yeshiva College of the Nation's Capital, the Torah School of Greater Washington, and The Barrie School.

Saint Francis International School St. Camillus Campus, serving kindergarten through 8th grade, is in Silver Spring.[75] It was formerly St. Camillus School, which was operated by sisters of Notre Dame de Namur and opened in 1954. In the middle of the 1960s it had up to 1,200 students. Working-class people were the main clientele. The student population was in decline by the 1980s as working-class people moved from the area. By the same decade the teachers were mostly lay staff. In the decade of the 2000s the school's financial situation deteriorated. In 2010 the school had 260 students. It merged into Saint Francis International, which opened in 2010; at that time all teachers had to reapply for their jobs. In 2010 Saint Francis International had 435 students at all campuses. In 2014 it had 485 students at all campuses; over 70% the students were of parents born abroad.[76]

Montgomery College

[edit]A portion of the Montgomery College, the Takoma Park/Silver Spring campus, is located in the Silver Spring; the rest of the campus located in Takoma Park. The community college is Montgomery County's main institute of higher education; the main campus is in the county seat of Rockville. The campus of the National Labor College is in the White Oak neighborhood in the outer reaches of Silver Spring.

Howard University

[edit]Howard University's School of Continuing Education is located in Silver Spring; its main campus in nearby Washington, D.C.

Libraries

[edit]Silver Spring is served by many public libraries:

- Brigadier General Charles E. McGee Library located in downtown Silver Spring.

- Connie Morrella (formerly Bethesda)

- Marilyn J. Praisner (formerly Fairland)[77]

- Wheaton

- White Oak[78] and Long Branch.[79]

Silver Spring Library started operation in 1931 and is one of the most heavily used in the Montgomery County System. It was relocated in June 2015 to Wayne Avenue and Fenton Street[80] as part of the Downtown Silver Spring redevelopment plan.

Economy

[edit]A number of major companies and organizations are based in Silver Spring, including:

- American Nurses Association, a professional organization

- CuriosityStream, a streaming media company

- Food and Drug Administration, a U.S. federal government agency

- Global Communities, an international development and humanitarian aid nonprofit[81]

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, a U.S. federal government agency

- Urban One, a media company

- United Therapeutics, a biotechnology company

Sports

[edit]The Silver Spring Saints Youth Football Organization has been a mainstay of youth sports in the town since 1951. Located in Silver Spring, the Silver Spring Saints play home games at St. Bernadette's Church near Blair High School. The club was formed when two local Catholic parishes, St. John the Baptist and St. Andrews, merged their football programs to compete in the Capital Beltway League after the CYO (Catholic Youth Organization) for the Archdiocese of Washington D.C. discontinued its youth football program at the end of the 1994 season. The name "Saints" is derived from the merging of the two Catholic parishes. In 2009, the Saints moved from the Capital Beltway League (CBL) to the Mid-Maryland Youth Football & Cheer League (MMYFCL).

Silver Spring is also home to several swim teams, including Parkland, Robin Hood, Calverton, Franklin Knolls, Daleview, Oakview, Forest Knolls, Kemp Mill, Long Branch, Stonegate, Glenwood, Rock Creek, and Northwest Branch, Hillandale, and West Hillandale.

Silver Spring and Takoma Park together host Silver Spring-Takoma Thunderbolts a college wooden-bat baseball team playing in the Cal Ripken, Sr. Collegiate Baseball League. Home games are played at Montgomery Blair Stadium.

The Potomac Athletic Club Rugby team has a youth rugby organization based in Silver Spring. Established in 2005, PAC Youth Rugby has tag rugby for ages 5 to 15, girls and boys and also offer introduction to tackle rugby for U13 and U15 players. In addition to introducing numerous young athletes to the sport of rugby, PAC has also won Maryland state championships across the age groups.

Media

[edit]Silver Spring is served by Washington metropolitan area media, including two daily newspapers, The Washington Post and The Washington Times, and several online outlets. The Gazette and the Montgomery County Sentinel were available historically until their closures in 2015 and 2020, respectively.

The Washington Hispanic has its offices in Silver Spring.[82]

Companies headquartered in Silver Spring include Urban One. After relocating to New York City in 2018, Discovery Inc. sold its former Silver Spring headquarters to Foulger-Pratt and Cerberus Capital Management, and leased a smaller space at nearby 8403 Colesville Road.[83][84]

Notable people

[edit]- Joe Alexander (b. 1986), American-Israeli basketball player in the Israel Basketball Premier League

- Elijah Amo (b. 1999), soccer player

- Brady Anderson (b. 1964), baseball player[85]

- Charles Arndt (b. 1967), soccer player and coach[86]

- Akil Baddoo (b. 1998), baseball player for the Detroit Tigers[87]

- Jonathan Banks (b. 1947), actor[88]

- Alex Bazzie (b. 1990), football player[89]

- Carl Bernstein (b. 1944), journalist, writer[90]

- Keter Betts (1928–2005), musician[91]

- Lewis Black (b. 1948), comedian[92]

- Brandon Broady (b. 1986), comedian, television host[93]

- Laphonza Butler, U.S. senator[94]

- Bill Callahan (b. 1966), musician[95]

- Rachel Carson (1907–1964), author of Silent Spring[96]

- Crystal Chappell (b. 1965), actress[97]

- Dave Chappelle (b. 1973), comedian[98]

- Connie Chung (b. 1946), news presenter[99]

- Gaelan Connel (b. 1989), actor, musician[100]

- Chuck Davidson (b. 1961), rabbi

- Tommy Davidson (b. 1963), comedian, actor[101]

- Marc Davis (b. 1990), NASCAR driver[102]

- Dominique Dawes (b. 1976), gymnast, 4-time Olympic medalist[103]

- Cara DeLizia (b. 1984), actress[104]

- Matt Drudge (b. 1966), internet news editor[105]

- Michael Ealy (b. 1973), actor[106]

- Neil Fallon, lead singer for the band Clutch

- Wayne Federman (b. 1959), comedian, actor, writer[107]

- Charles Fefferman (b. 1949), mathematician[108]

- David Feldberg (b. 1977), professional disc golfer[109]

- Martin Felsen (b. 1968), architect[110]

- John Meredith Ford (1923–1995), Guyanese politician; died in Silver Spring

- Steve Francis, former basketball player

- Jason Freeny (b. 1970), sculptor, toy designer[111]

- Kimmy Gatewood, actress, writer and singer[112]

- Emily Gould (b. 1981), author[113]

- Jerian Grant (b. 1992), basketball player for the Washington Wizards

- Josh Hart (b. 1995), basketball player for the New York Knicks; first-round selection in 2017 NBA draft

- Goldie Hawn (b. 1945), actress, dancer, producer, and singer

- Keith Howland (b. 1964), musician (Chicago)[114]

- Frank Jackson (b. 1998), NBA player

- Rian Johnson (b. 1973), film director

- Jesse Mockrin (b. 1981), artist[115]

- Amir Mohamed el Khalifa (stage name: Oddisee), rapper

- Humayun Khan (1976 – 2004), U.S. Army Officer of Pakistani descent and a Muslim, posthumous recipient of the Purple Heart and the Bronze Star Medal.

- Rick Leventhal (b. 1960), journalist

- Elliot Levine (b. 1963), musician (Heatwave)[116]

- Dov Lipman (b. 1971), member of the Knesset[117]

- Matt Maloney (b. 1971), former basketball player

- Michelle M. Marciniak (b. 1973), former WNBA professional basketball player and collegiate coach

- Roger Mason Jr. (b. 1980), former basketball player

- Joey Mbu (b. 1993), football player[118]

- Victor Oladipo (b. 1992), basketball player for the Houston Rockets[119]

- George Pelecanos (b. 1957), author[120]

- Al Quie (b. 1923), former Governor of Minnesota (1979–1983)[121]

- Gretchen Quie (1927–2015), artist and former First Lady of Minnesota (1979–1983)[121]

- J. Robbins (b. 1967), musician (Jawbox, Office of Future Plans)[122]

- Nora Roberts (b. 1950), novelist[123]

- Daniel Snyder (b. 1964), businessperson and former owner of the Washington Commanders

- Harold Solomon (b. 1952), tennis player ranked No. 5 in the world[124]

- Norman Solomon (b. 1951), journalist, political candidate[125]

- Ben Stein (b. 1944), commentator, humorist, actor[126]

- Rebecca Sugar (b. ca. 1987), artist, composer, and director[127]

- Daryush Valizadeh (b. 1979), neomasculinity writer

- Thalia Zedek (b. 1961), musician (Live Skull, Come)[128]

See also

[edit]- Washington metropolitan area

- Montgomery County, Maryland

- Silver Spring Library

- Montgomery County Public Libraries

- Montgomery County Public Schools

- Montgomery College

- Silver Spring Monkeys

- List of sundown towns in the United States

References

[edit]- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on March 5, 2023. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Silver Spring, Maryland

- ^ Garreau, Joel (1991). "Chapter 11: The List: Edge Cities Coast to Coast". Edge City: Life on the New Frontier (1st ed.). New York, NY: Doubleday. pp. 425–438. ISBN 978-0-385-26249-1. LCCN 91010548. OCLC 246864569. OL 1532880M. Archived from the original on January 7, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2019.

- ^ a b c "QuickFacts: Silver Spring CDP, Maryland". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved August 17, 2021.

- ^ "Geographic Comparison Table, 2010 Census Redistricting Data Summary File, Maryland: By Place". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on December 27, 1996. Retrieved June 17, 2011.

- ^ United States Census Bureau (2017). 2013–2017 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates. Silver Spring CDP, Maryland. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

Margin of Error ±1,785.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Silver Spring Regional Center – Downtown Silver Spring". Montgomerycountymd.gov. February 3, 2006. Archived from the original on March 4, 2010. Retrieved July 17, 2009.

- ^ a b "Acorn Urban Park". MontgomeryParks.org. October 30, 2018. Archived from the original on January 26, 2019. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

According to local history, in 1840 a newspaper publisher and friend of President Andrew Jackson, Francis Preston Blair, discovered the spring bubbling up through shiny mica sand.

- ^ a b Sheir, Rebecca (April 4, 2014). "The Man Who Discovered Silver Spring's 'Silver Spring'". Washington, D.C.: WAMU 88.5 – American University Radio. Archived from the original on January 26, 2019. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

Silver Spring Historical Society president Jerry McCoy at Acorn Park: the site thought to be where Preston Blair discovered the original 'silver spring'.

- ^ a b "A Brief History of Silver Spring" (PDF). MontgomerySchoolsMD.org. Cannon Road Elementary School, Montgomery County Public Schools. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 26, 2019. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

Acorn Park, tucked away in an area of south Silver Spring away from the main downtown area, is believed to be the site of the original spring.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Archived from the original on August 24, 2019. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "White Oak Campus Information". US FDA. Archived from the original on April 21, 2016. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- ^ "Best Natural Areas – Northwest Branch Stream Valley Park". Montgomery Parks. September 13, 2011. Archived from the original on April 23, 2016. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ^ Montgomery County Parks. "Educational Interpretive Signs" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on January 19, 2018.

- ^ "MNCPPC: Jesup Blair Local Park". Archived from the original on June 30, 2009. Retrieved January 7, 2007.

- ^ Collins, Donald Earl (September 25, 2010). "Jessup-Blair Park Sign, Silver Spring-Washington DC border". DonaldEarlCollins.com. Archived from the original on January 26, 2019. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

- ^ "CENSUS OF POPULATION AND HOUSING (1790–2000)". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 1, 2021. Retrieved July 17, 2010.

- ^ a b "Silver Spring, MD: Census Place". Data USA. Archived from the original on May 23, 2022. Retrieved May 8, 2022.

- ^ a b c U.S. Census Bureau (April 1, 2010). Geography: Silver Spring CDP, Maryland – DP-1 – Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 – 2010 Demographic Profile Data. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Rastogi, Sonya; Johnson, Tallese D.; Hoeffel, Elizabeth M.; Drewery, Jr., Malcolm P. (September 2011). The Black Population: 2010 (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 31, 2019. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Norris, Tina; Vines, Paula L.; Hoeffel, Elizabeth M. (January 2012). "The American Indian and Alaska Native Population: 2010" (PDF). 2010 Census Briefs. U.S. Census Bureau. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 5, 2019. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

- ^ U.S. Census Bureau (January 2017). "Race & Ethnicity" (PDF). Census.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 18, 2019. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

- ^ "The Demographic Statistical Atlas of the United States - Statistical Atlas". statisticalatlas.com. Archived from the original on June 4, 2021. Retrieved April 22, 2022.

- ^ Reed, Dan (September 14, 2015). "DC's "Little Ethiopia" has moved to Silver Spring and Alexandria". GreaterGreaterWashington.org. Archived from the original on April 27, 2016. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ^ "American FactFinder - Results". Archive.today. Archived from the original on February 10, 2020. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

- ^ "APPROVED AND ADOPTED NORTH and WEST SILVER SPRING MASTER PLAN" (PDF). The Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 10, 2022. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Sween, Jane C.; Offutt, William. Montgomery County: Centuries of Change. American Historical Press, 1999. ISBN 1-892724-05-7.

- ^ McCoy, Jerry A. (August 2003). "Silver Spring Then & Again". Takoma Voice. Archived from the original on August 3, 2004. Retrieved March 3, 2009.

- ^ McCoy, Jerry A. (February 6, 2009). "Abe Lincoln in Silver Spring". Silver Spring Voice. Archived from the original on February 11, 2009. Retrieved March 3, 2009.

- ^ "Interesting Particulars of the Rebel Invasion". Evening Star. July 15, 1864. p. 2. Archived from the original on February 7, 2024. Retrieved September 25, 2014.

- ^ "The Metropolitan Railroad". The Evening Star. April 30, 1873. p. 4. Archived from the original on February 7, 2024. Retrieved September 25, 2014.

- ^ Dunaway, Karen. "Edward Brooke Lee". Archives of Maryland (Biographical Series). Maryland State Government. Archived from the original on November 13, 2014. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- ^ "Work Being Pushed at Woodside Park". The Washington Post. April 15, 1923. p. 46. ProQuest 149333195.

- ^ "Jewish Washington: Scrapbook of an American Community | Real Estate Boom". Jhsgw.org. Archived from the original on June 4, 2016. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ^ "Silver Spring Shopping Center Opens Today: Comprises 19 Stores, Gas Station, Movie". The Washington Post. October 27, 1938. p. SS1. ProQuest 151050489.

- ^ "Immigration and Success | Montgomery County Historical Society Maryland". Archived from the original on October 22, 2014. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- ^ "Downtown Silver Spring". ArcGIS StoryMaps. December 13, 2019. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved August 23, 2020.

- ^ Rotenstein, David (September 24, 2018). "Racial restrictive covenants renounced at celebration". History Sidebar. Archived from the original on August 17, 2020. Retrieved August 23, 2020.

- ^ Editorial Board (June 23, 2017). "Protesting Invisibility in Silver Spring, Maryland". The Activist History Review. Archived from the original on September 24, 2020. Retrieved August 23, 2020.

- ^ "Sixteenth Street Village". Montgomery Planning. Archived from the original on February 8, 2024. Retrieved June 12, 2024.

- ^ "Attachment A" (PDF). Montgomery Planning. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 16, 2024. Retrieved June 14, 2024.

- ^ Woldu, Marta Woldu; Ramirez, Christopher (December 13, 2019). "Downtown Silver Spring: Inclusivity Examined Since 1940". ArcGIS StoryMaps. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved June 17, 2024.

- ^ Bradley, Wendell P. (December 20, 1961). "Tawes Vows Study of Beltway Impact at Road's Opening: Study to Dispel Myth". The Washington Post. p. C1. ProQuest 141415305.

- ^ "Historic Overview: Capital Beltway". Eastern Roads (Steve Anderson). March 16, 2008. Archived from the original on October 4, 2008. Retrieved October 5, 2008.

- ^ "Capital Beltway History". Scott M. Kozel. November 20, 2007. Archived from the original on December 8, 2008. Retrieved October 5, 2008.

- ^ "Executive Records, Governor J. Millard Tawes, 1959–1967". Maryland State Archives. August 17, 1964. Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved October 5, 2008.

- ^ Causey, Mike (August 18, 1964). "Throng Attends Capital Beltway's Grand Opening". The Washington Post. p. A1. ProQuest 142191843.

- ^ "State officials study HOV lanes for Capital Beltway". The Gazette. September 24, 1997. Archived from the original on May 22, 2011. Retrieved October 9, 2008.

- ^ "Silver Spring: Story of an American Suburb (2002)". IMDb. December 6, 2002. Archived from the original on April 5, 2016. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ^ Abha Bhattarai. "Discovery Communications is selling Md. headquarters and moving to New York". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 18, 2018. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- ^ "Takoma Voice: News". Takoma.com. Archived from the original on August 23, 2004. Retrieved July 17, 2009.

- ^ Eugene L. Meyer, "A Dose of Art and Entertainment Revives a Suburb" Archived September 20, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, June 13, 2007

- ^ Shibley, Robert; Axelrod, Emily; Farbstein, Jay; Wener, Richard (2005). Downtown Silver Spring and Discovery Communications world headquarters. Silver medal winner (PDF). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Bruner Foundation. pp. 47–78. ISBN 1-890286-07-9. OCLC 71837571. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 3, 2020.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "Rudy Bruner Award: Downtown Silver Spring". www.rudybruneraward.org. Bruner Foundation. Archived from the original on April 3, 2020. Retrieved April 3, 2020.

- ^ Marc Fisher, "Public or Private Space? Line Blurs in Silver Spring" Archived October 7, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, The Washington Post, June 21, 2007

- ^ Ruben Castaneda, "County Opinion Rejects Photo Limits" Archived December 2, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, The Washington Post, July 31, 2007

- ^ "Next Stop: Silver Spring". Silverspringtrain.blogspot.com. September 3, 1964. Archived from the original on August 27, 2011. Retrieved July 17, 2009.

- ^ "Next Stop: Silver Spring – Trailer". YouTube. November 15, 2007. Archived from the original on June 19, 2013. Retrieved July 17, 2009.

- ^ Diegel, Mike (May 21, 2019). "Downtown Silver Spring to Get $10 Million Renovation, New Tenants". Source of the Spring. Archived from the original on October 20, 2020. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ^ "The Filmore Silver Spring". JamBase. Archived from the original on February 5, 2020. Retrieved February 5, 2020.

- ^ "Stevie Nicks on Silver Springs". Archived from the original on June 23, 2018. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

- ^ Mosk, Matthew (July 12, 2005). "Once Politically Divisive, ICC Slowly Gained Favor". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 4, 2016. Retrieved January 28, 2016.

- ^ Shaver, Katherine; Hosh, Kafia A. (February 23, 2011). "ICC toll road opens to traffic". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 3, 2013. Retrieved January 28, 2016.

- ^ Schwind, Dan (November 22, 2011). "ICC opens second segment, connecting Laurel to Gaithersburg". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on February 12, 2016. Retrieved January 28, 2016.

- ^ Rector, Kevin (November 22, 2011). "Final section of ICC to Laurel, new I-95 interchange to open this weekend". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved January 28, 2016.

- ^ Thomson, Robert (November 19, 2011). "User's guide to Intercounty Connector". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 4, 2016. Retrieved January 28, 2016.

- ^ "MCDOT Projects: Silver Spring Transit Center (SSTC)". Archived from the original on October 6, 2008. Retrieved September 26, 2008.

- ^ "Metro – Bus – Paul S. Sarbanes Transit Center in Silver Spring". Wmata.com. Archived from the original on December 9, 2015. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- ^ Essner, Dean (September 16, 2015). "A Timeline of Failure for the Silver Spring Transit Center". The Washingtonian. Archived from the original on June 23, 2023. Retrieved June 23, 2023.

- ^ Shaver, Katherine (January 26, 2022). "Md. board approves $3.4 billion contract to complete Purple Line". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 12, 2022. Retrieved July 2, 2022.

- ^ Rosenthal, Josh (March 1, 2024). "Purple Line opening delayed to winter 2027". FOX 5 DC. Archived from the original on June 10, 2024. Retrieved June 10, 2024.

- ^ "Lee Middle School to be renamed Odessa Shannon Middle School". Bethesda Magazine. November 10, 2020. Archived from the original on November 11, 2020. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ^ "2010 CENSUS – CENSUS BLOCK MAP: Four Corners CDP, MD" (Archive). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- ^ "Census 2000 Block Map: Silver Spring CDP" (Archive). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved June 22, 2015. Detail 1 (Archive), Detail 2 (Archive)

- ^ "Contact Us Archived January 31, 2018, at the Wayback Machine." Saint Francis International School. Retrieved January 31, 2018. "1500 St. Camillus Drive Silver Spring, MD 20903"

- ^ Roberts, Tom. "Maryland Catholic school finds its footing amid demographic shifts Archived February 1, 2018, at the Wayback Machine." Catholic Standard, Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Washington. Wednesday, October 15, 2008. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

- ^ "MCPL: Wheaton Library". Montgomerycountymd.gov. Archived from the original on July 19, 2009. Retrieved July 17, 2009.

- ^ "MCPL: White Oak Library". Montgomerycountymd.gov. February 4, 2009. Archived from the original on October 3, 2003. Retrieved July 17, 2009.

- ^ "MCPL: Long Branch Library". Montgomerycountymd.gov. May 13, 2009. Archived from the original on April 30, 2009. Retrieved July 17, 2009.

- ^ Michelle Chavez (January 16, 2015). "Negotiations for Arts Center at New Silver Spring Library Fall Through". 4 NBC Washington. Archived from the original on December 21, 2015. Retrieved September 24, 2016.

- ^ "Home | Global Communities". Archived from the original on March 21, 2019. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- ^ "__ Washington Hispanic __". Archived from the original on March 8, 2013. Retrieved March 19, 2013.

- ^ Diegel, Mike (September 6, 2018). "Discovery Sells Silver Spring Headquarters Building". Source of the Spring. Archived from the original on October 12, 2020. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ Clabaugh, Jeff (September 6, 2018). "Discovery leases Silver Spring space for new Md. operations". WTOP. Archived from the original on March 25, 2023. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ "Brady Anderson Stats". Baseball Almanac. Archived from the original on November 4, 2012. Retrieved December 3, 2012.

- ^ "Men's Soccer to Retire Charlie Arndt's Jersey". South Carolina Gamecocks. September 6, 2023. Retrieved December 29, 2024.

- ^ "Akil Baddoo Minor & Amateur Leagues Statistics & History". Baseball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on November 10, 2021. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

- ^ Dalsheim, Hannah (September 23, 2019). "Julia Louis-Dreyfus, Other Montgomery County Natives Nominated For Emmys". Montgomery Community Media. Archived from the original on September 22, 2021. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- ^ Rogers, Adam (June 25, 2014). "Pro dreams become a reality for Herd's Bazzie". marshallparthenon.com. Archived from the original on August 12, 2014. Retrieved August 11, 2014.

- ^ "IMDB entry for Carl Bernstein". IMDb. Archived from the original on August 21, 2013. Retrieved December 9, 2012.

- ^ "Bassist Keter Betts Dies at Age 77". JazzTimes. August 8, 2005. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved August 8, 2005.

- ^ "Lewis Black Is One Angry Comic". CBS News. November 5, 2006. Archived from the original on June 16, 2007. Retrieved December 13, 2006.

- ^ Bartel (February 25, 2015). "Towson University grad Brandon Broady hosting new BET series". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on February 26, 2015. Retrieved February 25, 2015.

- ^ Phillips, Aleks (October 2, 2023). "Laphonza Butler's non-California residence raises questions". Newsweek. Archived from the original on October 2, 2023. Retrieved October 3, 2023.

- ^ Ben Ratliff (April 8, 2011). "He Can Sing It, if Not Speak Its". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 2, 2013. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- ^ "Rachel Carson biography". Women in History. Archived from the original on August 8, 2012. Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- ^ "IMDB entry for Crystal Chappell". IMDb. Archived from the original on January 5, 2013. Retrieved December 9, 2012.

- ^ "Dave Chappelle". Inside the Actors Studio. episode 10. season 12. February 12, 2006. Bravo.

- ^ "IMDB entry for Connie Chung". IMDb. Archived from the original on December 25, 2013. Retrieved December 9, 2012.

- ^ Ramanathan, Lavanya (August 11, 2009). "From Basement to 'Bandslam'". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 8, 2012. Retrieved August 11, 2009.

- ^ Davidson, Tommy; Teicholz, Tom (2020). Living in Color. Kensington Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4967-1294-3.

- ^ "Davis to Ring Bell at New York Stock Exchange". NASCAR. Archived from the original on November 3, 2013. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ Mary Buckheit (February 22, 2008). "Catching up with Dominique Dawes". ESPN. Archived from the original on February 29, 2008. Retrieved February 22, 2008.

- ^ "IMDB entry for Cara DeLizia". IMDb. Archived from the original on February 24, 2013. Retrieved March 23, 2013.

- ^ Eddie Dean (March 13, 1998). "Hard Times and Jalapeño Bologna Internet rebel Matt Drudge's early years". Washington City Paper. Archived from the original on October 15, 2012. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- ^ "IMDB entry for Michael Ealy". IMDb. Archived from the original on November 9, 2012. Retrieved December 9, 2012.

- ^ "IMDB entry for Wayne Federman". IMDb. Retrieved October 9, 2020.[dead link]

- ^ Richard K. Rein (October 15, 1979). "Like His Daughter, Nina, Princeton Math Genius Charlie Fefferman Just Eats Up Numbers". People. Vol. 12, no. 16. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- ^ "David Feldberg #12626". Pdga.com. Archived from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

- ^ "Martin Felsen biography". National Building Museum. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved September 23, 2014.

- ^ "Artist Jason Freeny transforms familiar childhood characters into realistic anatomical models". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on January 15, 2014. Retrieved January 14, 2014.

- ^ Jackson, Christine (July 11, 2017). "GLOW's Kimmy Gatewood Talks Comedy, Big Hair, and the Joys of Wrestling". Washingtonian. Archived from the original on September 20, 2017. Retrieved July 16, 2017.

- ^ "And the Heart Says Whatever". Publishers Weekly. Archived from the original on July 1, 2014. Retrieved September 26, 2014.

- ^ "All Voices entry for Keith Howland". allvoices.com. Archived from the original on April 23, 2013. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- ^ "Jesse Mockrin - Artists - Night Gallery". www.nightgallery.ca. Archived from the original on June 30, 2024. Retrieved June 30, 2024.

- ^ "Jazz festival expected to bring thousands to Silver Spring Saturday". The Gazette. August 8, 2005. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved September 4, 2012.

- ^ Ahren, Raphael (February 19, 2013). "Dov Lipman's rock solid struggle for a better Israel". The Times of Israel. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ^ "Joey Mbu". National Football League. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ^ "NBA No. 5 Victor Oladipo". ESPN. Archived from the original on April 22, 2016. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ^ Walker Lamond. "DC Confidential". Stop Smiling. Archived from the original on December 5, 2008. Retrieved September 21, 2008.

- ^ a b Salisbury, Bill (December 14, 2015). "Gretchen Quie, opened governor's house to public, dies at 88". St. Paul Pioneer Press. Archived from the original on January 2, 2016. Retrieved January 2, 2016.

- ^ "J. Robbins' resonance remains felt in rock circles". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on December 27, 2014. Retrieved September 25, 2014.

- ^ Vernon, Cheril (July 22, 2007), "'Queen of Romance' still going strong", Palestine Herald-Press, archived from the original on January 11, 2013, retrieved August 8, 2007

- ^ "Tennis, Life Are Growing On Solomon". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved May 17, 2018.

- ^ "Norman Solomon Interview". November 27, 2007. Archived from the original on April 2, 2014. Retrieved September 25, 2014.

- ^ Stein, Joel (November 28, 1999). "Ben Stein Also Sings". Time. Archived from the original on June 15, 2013. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ^ Cavna, Michael (November 1, 2013). "'Steven Universe' creator Rebecca Sugar is a Cartoon Network trailblazer". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 11, 2013. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- ^ "All Music reference". AllMusic. Archived from the original on October 16, 2015. Retrieved December 22, 2014.

Further reading

[edit]- McCoy, J, et al. (2003). Silver Spring Timeline. Retrieved August 6, 2003 from "Silver Spring history".

- McCoy, Jerry A. and Silver Spring Historical Society. Historic Silver Spring. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2005.

- McCoy, Jerry A. (October 20, 2010). Downtown Silver Spring. Then & now. Silver Spring Historical Society (Silver Spring, Md.). Charleston, S.C.: Arcadia Pub. ISBN 978-0-7385-8631-1. LCCN 2010923962. OCLC 644650590.

- Susan Soderberg (February 2011). "Downtown Silver Spring". H-Net Reviews (Review).

External links

[edit]Documentary films

[edit]- Silver Spring, Maryland

- 1887 establishments in Maryland

- Census-designated places in Maryland

- Census-designated places in Montgomery County, Maryland

- Edge cities in the Baltimore-Washington metropolitan area

- Sundown towns in Maryland

- Unincorporated communities in Montgomery County, Maryland

- Unincorporated communities in Maryland