Bangor, Gwynedd

| Bangor | |

|---|---|

| Town and community | |

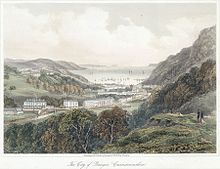

View of the Town from Porth Penrhyn in 2019 | |

Coat of arms | |

| Area | 2.5 sq mi (6.5 km2) |

| Population | 15,060 (Community, 2021)[1] 16,990 (Built up area, 2021)[2] |

| Demonym | Bangorian |

| OS grid reference | SH 580722 |

| • Cardiff | 127 mi (204 km) SSE |

| • London | 207 mi (333 km) SE |

| Principal area | |

| Preserved county |

|

| Country | Wales |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | BANGOR |

| Postcode district | LL57 |

| Dialling code | 01248 |

| Police | North Wales |

| Fire | North Wales |

| Ambulance | Welsh |

| UK Parliament | |

| Senedd Cymru – Welsh Parliament | |

| Website | bangorcitycouncil |

Bangor (/ˈbæŋɡər, -ɡɔːr/;[3][4] Welsh: [ˈbaŋɡɔr] ⓘ) is a cathedral city and community in Gwynedd, North Wales. It is the oldest town in Wales. Historically part of Caernarfonshire, the community had a population of 15,060 at the 2021 census, and the built up area had a population of 16,990. Landmarks include Bangor Cathedral, Bangor University and Garth Pier. The Britannia and Menai Suspension bridges connect the city to the Isle of Anglesey.

History

[edit]

The origins of the city date back to the founding of a monastic establishment on the site of Bangor Cathedral by the Celtic saint Deiniol in the early 6th century AD. 'Bangor' itself is an old Welsh word for a wattled enclosure,[5] such as the one that originally surrounded the cathedral site. The present cathedral is a somewhat more recent building and has been extensively modified throughout the centuries. While the building itself is not the oldest, and certainly not the biggest, the bishopric of Bangor is one of the oldest in the UK.

In 973, Iago, ruler of the Kingdom of Gwynedd, was usurped by Hywel, and requested help from Edgar, King of England, to restore his position. Edgar, with an army, went to Bangor and encouraged both Iago and Hywel to share the leadership of the realm. Asserting overall control however, Edgar confirmed liberties and endowments of the Bishop of Bangor, granting land and gifts. From 1284 until the 15th century, Bangor bishops were granted several charters permitting them to hold fairs[6] and govern the settlement, later ones also confirming them as Lord of the Manor.[7]

Bangor remained a small settlement until the start of the 18th century. The main mail coach route from London to Dublin via Holyhead passed to the east of Bangor, crossing the Lavan Sands to reach a ferry across the Menai Strait to Beaumaris. In 1718 a sub-postmaster was appointed based in Bangor and the mail coach route was diverted to pass through Bangor on its way to the alternative Porthaethwy ferry. Being on the mail coach route considerably increased the trade passing through Bangor and encouraged its growth.[8][7] Development was further spurred by slate mining at nearby Bethesda, beginning in the 1770s by Richard Pennant, becoming one of the largest slate quarries in the world. The route between London and Holyhead was much improved by Thomas Telford building the A5 road; it runs through the centre of the city and over the Menai Suspension Bridge, which was also completed to his designs in 1826. Bangor railway station opened in 1848.

Bangor's status grew due to further industry, such as shipbuilding,[9] as well as travel, not just from Telford's road, but through tourism mainly from Liverpool via steamboat.[10]

Friars School was founded as a free grammar school in 1557 and the University College of North Wales (now Bangor University) was founded in 1884. In 1877, the former HMS Clio became a school ship, moored on the Menai Strait at Bangor and had 260 pupils. Closed after the end of hostilities of World War I, she was sold for scrap and broken up in 1919.

In World War II, parts of the BBC evacuated to Bangor during the worst of the Blitz.[11] The BBC continue to maintain facilities in the city (see Media).

City status

[edit]Bangor is the only place in Wales which continues to hold city status by ancient prescriptive right, due to its long-standing cathedral and past privileges granted.[12] St Davids had also been a city by prescriptive right, but lost its status in the 1880s and was only formally restored to city status in 1994.[13] In 1927 a government list was drawn up detailing which settlements were cities, with Bangor being included as the only medieval Welsh city with extant rights.[14]

By means of various measures, Bangor is one of the smallest cities in the UK. Using 2011 statistics, comparing Bangor to:

- Population of city council areas in Wales, is third smallest (18,322 residents)[15] with St Davids (1,841) and St Asaph (3,355).

- City council area size within Wales, is the second smallest city (2.79 square miles (7.2 km2)) behind St Asaph (2.49 square miles (6.4 km2)).

- Urban areas within Wales, is third smallest, placed (1.65 square miles (4.3 km2)) behind St Davids (0.23 square miles (0.60 km2)) and St Asaph (0.50 square miles (1.3 km2))

- City council area size within the UK, is fourth smallest after the City of London (1.12 square miles (2.9 km2)), Wells and St Asaph.

- Urban areas within the UK, is fifth smallest.

- Population of city council areas within the UK, is sixth smallest.

Geography

[edit]Bangor lies on the coast of North Wales near the Menai Strait, which separates the island of Anglesey from Gwynedd, the town of Menai Bridge lying just over the strait. The combined population of the two amounted to 22,184 at the 2011 census. Bangor Mountain at 117 metres (384 ft) lies to the east of the main part of the city, but the large housing estate of Maesgeirchen, originally built as council housing, is to the east of the mountain near Port Penrhyn. Another ridge rises to the north of the High Street, dividing the city centre from the south shore of the Menai Strait; this area is known as Upper Bangor (Bangor Uchaf).

The Bangor community area includes the suburbs of Garth and Hirael both immediately north of the city centre; Upper Bangor north west of the centre; West End, Glan-adda, Bryn Llwyd and Coed Mawr to the south west; Y Maes to the south; Glantraeth, Tan-y-bryn and Maesgeirchen are to the east. The suburbs of Penhros-garnedd, Treborth and Minffordd are within the community of Pentir adjoining the city to the south and south west. Port Penrhyn and the tiny estate of Plas-y-coed, adjoin the city within the Llandygai community.

Bangor has two rivers within its boundaries. The River Adda is a largely culverted watercourse which only appears above ground at its western extremities near the Faenol estate, whilst the River Cegin enters Port Penrhyn at the eastern edge of the city. Port Penrhyn was an important port in the 19th century, exporting the slates produced at the Penrhyn Quarry.

Governance

[edit]

There are two tiers of local government covering Bangor, at community (city) and county level: Bangor City Council (Cyngor Dinas Bangor) and Gwynedd Council (Cyngor Gwynedd). The city council meets at Penrhyn Hall on Fford Gwynedd and has its offices in the adjoining building, which was built in 1866 as the Diocesan Registry.[16][17][18]

In 2021, Owen Hurcum was unanimously elected as mayor, making history as the youngest-ever mayor in Wales at 22, as well as the first ever non-binary mayor of any UK city.[19]

In 2012, Bangor was the first city in the UK to impose a night-time curfew on under-16s throughout its centre. The six-month trial was brought in by Gwynedd Council and North Wales police, but opposed by civil rights groups.[20]

Bangor lies within the Bangor Aberconwy constituency for elections to the UK parliament. Arfon is the constituency for elections to the Senedd.

Administrative history

[edit]Bangor was an ancient parish, which historically included a large rural area to the south and south-west of the city itself.[21] The city was sometimes described as an ancient borough and was said to hold certain privileges.[22] However, Bangor had no municipal charters and any corporation it may have had in medieval times did not endure. A government survey of boroughs in 1835 noted that it was plausible that Bangor may once have had a corporation, but found no evidence of any such corporation having operated for many years. Instead, Bangor was governed by the parish vestry and the Bishop of Bangor in his capacity as lord of the manor until the 19th century.[23][22]

In 1832, a parliamentary borough of Bangor was established as one of the boroughs which made up the Carnarvon Boroughs constituency.[24] The area of the parliamentary borough of Bangor was made a local board district in 1850, with an elected local board to govern the city.[25] Over time the local board gained more powers for managing local affairs, but by the 1870s it was seen as ineffective. A petition was made for the city to be formally incorporated as a municipal borough, which would give it more extensive powers of local government. A municipal charter incorporating the city was duly granted in 1883.[26][27] The Local Government Act 1894 directed that parishes could no longer straddle borough boundaries and so the part of Bangor parish outside the borough became the separate parish of Pentir.[28]

The municipal borough of Bangor was abolished in 1974 under the Local Government Act 1972. A community called Bangor was created instead, covering the area of the abolished borough. District-level functions passed to Arfon Borough Council, which was in turn replaced in 1996 by Gwynedd Council.[29][30] As part of the 1974 reforms, Bangor's city status, which had been held by the abolished borough, was transferred to the new community.[31]

Demography

[edit]Bangor is ethnically diverse, with 85% of the population identifying as White British, followed by 8% Asian or Arab, 3% Mixed Race, 2% Black and 2% other ethnic. This makes Bangor 85% white and 15% non-white, which means the city has one of the highest ethnicity populations in Wales for its population of over 15,000.[32][33]

In religion, Christianity was followed by 8,816 residents, Islam followed by 892 residents, and 6,526 residents not identifying with any religion or identifying with other religions. Christianity is the most prominent religion but the second largest group followed no religion.[32] In 2021, Muslims in Bangor complained that restrictions imposed in the city had left women unable to worship at the mosque during Ramadan, while arrangements, such as outdoor prayers, had been made in other parts of Wales .[34]

Transport

[edit]Bangor railway station is a stop on the North Wales Coast Line, between Crewe, Chester and Holyhead. Services are operated by Transport for Wales.[35]

Bus services are provided predominantly by Arriva Buses Wales; routes connect the city with Holyhead, Caernarfon and Llandudno.[36]

The A5 runs through the centre of Bangor; it connects Holyhead, Shrewsbury and London. The A55 runs immediately to the south of Bangor, providing a route to Holyhead and Chester.

The nearest airport with international flights is Liverpool John Lennon Airport, which is 83 miles (134 km) by road.

Bangor lies at the western end of the North Wales Path, a 60-mile (97 km) long-distance coastal walking route to Prestatyn. Cycle routes NCR 5, NCR 8 and NCR 85 of the National Cycle Network pass through the city.

Culture

[edit]Heritage and nature conservation

[edit]The head office of Gwynedd Archaeological Trust is located on Garth Road.[37] The Trust was established in 1974 and carries out surveys, outreach and education, and excavations across Gwynedd and Anglesey.

The North Wales Wildlife Trust is also based on Garth Road, and manages the nature reserves at Eithinog and Nantporth.[38]

Music and arts

[edit]

Classical music is performed regularly in Bangor, with concerts given in the Powis and Prichard-Jones Halls as part of the university's Music at Bangor concert series. The city is also home to Storiel (the new name for the Gwynedd Museum and Art Gallery), which is located in Bangor Town Hall.[39] A new arts centre complex, Pontio, the replacement for Theatr Gwynedd, was scheduled for completion in the summer of 2014,[40] but the opening was delayed until November 2015.[41]

Bangor hosted the National Eisteddfod in 1890, 1902, 1915, 1931, 1940 (through the medium of radio), 1943, 1971 and 2005, as well as an unofficial National Eisteddfod event in 1874.

Garth Pier

[edit]

Garth Pier is the second longest pier in Wales and the ninth longest in the British Isles, at 1,500 feet (460 m) in length. It was opened in 1893 and was a promenade pier for the amusement of holiday-makers, who could stroll among the pinnacle-roofed kiosks.

In 1914, the pier was struck by a vessel that had broken free of its moorings. The damaged section was repaired temporarily by the Royal Engineers but, when in 1922 a permanent repair was contemplated, it was found that the damage was more severe than had been thought. The repairs were made at considerable cost and the pier remained open until 1974, when it was nearly condemned as being in poor condition. It was sold for a nominal price to Arfon Borough Council who proposed to demolish it, but the County Council, encouraged by local support, ensured that it survived by obtaining Grade II Listed building status for it.[42]

When it was listed that year, the British Listed Buildings inspector considered it to be "the best in Britain of the older type of pier without a large pavilion at the landward end."[43] Restoration work took place between 1982 and 1988, and the pier was re-opened to the public on 7 May 1988.[42] In November 2011, essential repair work was reported to be required, the cost being estimated at £2 million. A grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund was sought but the application was rejected.[44]

Cathedral

[edit]

The Cathedral Church of St Deiniol is a Grade I Listed building and is set in a sloping oval churchyard. The site has been used for Christian worship since the sixth century but the present building dates from the twelfth century. It has a two-bay chancel, transepts, a crossing tower, a seven-bay nave and a tower at the west end.[45]

Theatre

[edit]

The 344-seat Theatr Gwynedd was opened on Deiniol Road in 1975 by the university and closed in 2008; the building was demolished in 2010.[46] Prior to Theatr Gwynedd, Bangor was home to the County Theatre, a converted chapel on Dean Street. The building was altered in 1912 for theatrical productions and converted to Trilogy Nightclub in 1986.[47]

The Pontio Arts and Innovation Centre by Bangor University on Deiniol Road, opened in 2015, has a theatre and a one screen cinema.

The Archdeacon's House in Bangor was the setting for act 3, scene I of William Shakespeare's Henry IV, Part 1.[48]

Cinemas

[edit]Bangor once housed two cinemas:

- The Electric Pavilion – later Arcadia Cinema – stood on the High Street close to the station from about 1910 to 1930. This site was redeveloped for The Plaza Cinema, which operated from 1934 to 2006.[49] A new building was built on the site and is now occupied by Ty Willis student accommodation and a Domino's branch.

- The City Cinema opened in 1919, at 130–132, High Street. Building work started in 1914, but was likely delayed because of the war. The cinema closed in 1983, although the building is still there and is now occupied by a dance academy and a snooker club.[50]

A one-screen cinema opened as part of the Pontio building in 2015.

Recreation

[edit]Bangor has two King George V fields; these are located on Beach Road and Heol Dewi.

Retail trade

[edit]A claim to fame is that Bangor has the longest High Street in Wales at 1.265 km (0.79 mi).[51] Bangor has a central shopping area around the High Street and retail outlets on Caernarfon Road, on the outskirts of the city. One of these is St. David's Retail Park, built on the site of the demolished St David's maternity hospital.

In 1865, Morris Wartski, a refugee from the Tsarist pogroms, first established a jewellery business on Bangor's High Street and then a drapery store. His son, Isidore, went on to develop the drapery business and to create a large, fashionable store. He also redeveloped the Castle Inn on High Street in Bangor, which then became the high-class Castle Hotel. Wartski was a very popular mayor of the city and a great patron of local sports and charities. Wartski Fields were bequeathed to the city and people of Bangor by his widow, Winifred Marie, in memory of Isidore Wartski.

Welsh language

[edit]Gwynedd is the most Welsh-speaking county in Wales, with 65.4% of people saying they could speak it at the 2011 Census, although Bangor has been significantly more anglicised than its hinterland and the rest of Gwynedd, mostly because of the large student population. While nearby towns in Gwynedd, such as Bethesda and Caernarfon, were still 75–80% Welsh speaking in 2011,[52] Bangor was already only 53.4% Welsh speaking as early as 1971.[53]

In 2011, only 36% of the population of Bangor said they could speak Welsh; a significant decrease from the 46% recorded at the 2001 Census.[54][55] In 2015, of primary school pupils 5 years and over, the following percentages spoke Welsh fluently at home:[56]

- Ysgol Ein Harglwyddes – < 3%

- Ysgol Cae Top – < 3%

- Ysgol Hirael – 10%

- Ysgol Glancegin – 14%

- Ysgol Llandygai – 17%

- Ysgol Y Faenol – 23%

- Ysgol Y Garnedd – 61%

The city has long been the most cosmopolitan settlement in Gwynedd, attracting incomers from both England and further afield, with Bangor University being a key institution. At the 2011 Census, 49.3% of Bangor's population was born outside Wales.[54][55] Nevertheless, Welsh was the majority vernacular of the city in the 1920s and 1930s; at the 1921 Census, 75.8% of Bangor's inhabitants could speak Welsh with 68.4% of those aged 3–4 being able to, indicating that Welsh was being transmitted to the youngest generation in most homes.[57] The 1931 Census showed little change, with 76.1% of the overall population being able to speak Welsh.[58]

Education

[edit]Bangor University and Coleg Menai are located in the city. There are a few secondary schools, these include Ysgol Friars, Ysgol Tryfan and St. Gerard's School. There are also a number of primary and infant schools. Ysgol Y Faenol, Ysgol Y Garnedd and Ysgol Cae Top are all primary schools.

Hospital

[edit]

Ysbyty Gwynedd is located in Bangor in the suburb of Penrhosgarnedd. It has 403 beds, making it smaller than the other district general hospitals in Betsi Cadwaladr University Health Board (after Wrexham Maelor Hospital with 568 beds and Glan Clwyd Hospital near Rhyl with 424 beds.[59]

The former Caernarfon and Anglesey General Hospital[60] operated from 1809 to 1984 in Upper Bangor, on the site now occupied by Morrisons supermarket.

Sport

[edit]Bangor has a long-established football team, Bangor City F.C. which currently competes in the Cymru North, the second tier of Welsh football. Bangor City won the Welsh Premier League on three occasions (1994, 1995, 2011) and were continuous members of the league from its inception until 2018. Bangor City have also won the Welsh Cup eight times, most recently in the 2010 competition. Before 1992, they were members of the English football pyramid, peaking with the Northern Premier League title in 1982 and being FA Trophy runners-up in 1984. They have also competed in the UEFA Cup Winners' Cup three times (including its final season, 1998–99, before being merged into the UEFA Cup), UEFA Champions League twice and UEFA Cup five times, though they have not progressed far in any of the European competitions.

Fans wanting to protect football in the city, formed a breakaway club called Bangor 1876 F.C. in the summer of 2019 and, on 19 June 2019, the FAW announced the new club had been accepted into the Gwynedd League for the 2019–20 season.

Bangor is also home to rugby union team Bangor RFC who play in the WRU Division Two North league. As well as the city's team, the university boasts a very competitive rugby union team, which won the title in its BUCS league in the 2015-16 season and also undefeated in 2022 and 2023. The university's rugby team shares a performance and development programme with Rygbi Gogledd Cymru (RGC), who are the regional representative club for the North Wales Rugby Development Region.

Media

[edit]The Bangor Aye is an independent online news and information service for the city and surrounding area.

Bangor is home to a small BBC broadcasting centre, producing a large amount of output for BBC Radio Cymru. The studios are also the main North-West Wales newsroom for television, radio and on-line. The BBC's Light Entertainment Department moved to Bangor during World War II and many classic programmes (like It's That Man Again) came from Bangor.

Bangor was also previously home to two commercial radio stations, Heart Cymru (now Capital Cymru) (serving Anglesey and Gwynedd) and the now-defunct Heart North Wales Coast (now Capital North West and Wales) (serving the North Wales Coast), which shared studio facilities on the Parc Menai office complex; the studios were closed in August 2010 after the stations were moved to Wrexham.

Bangor University also has its own student radio station called Storm FM, which broadcasts to the Ffriddoedd Site and from their website.

In 1967, The Beatles came to Bangor, staying in Dyfrdwy, one of the halls comprising Adeilad Hugh Owen (Hugh Owen Building), now part of the Management Centre, for their first encounter with Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, during which visit they learned of the death of their manager Brian Epstein.[61][62]

On 24 February 2010, BBC Radio 1's The Chris Moyles Show announced Bangor as the location for Radio 1's Big Weekend concert festival. The morning show was broadcast on location from Bangor, with the announcement as well as a portion of the lineup being revealed. International acts such as Rihanna, MGMT, Kesha and Alicia Keys played as well as homegrown British acts such as Biffy Clyro, Pixie Lott, Cheryl Cole, Pendulum and Dizzee Rascal.[citation needed]

The town is mentioned in the Fiddler's Dram 1979 hit single "Day Trip to Bangor". The release was shrouded in controversy after reports that the song was actually inspired by a trip to nearby Rhyl; there were rumours of an outcry among local councillors and businesses in Rhyl about the missed opportunity for tourism which would have been generated. Songwriter Debbie Cook stated that the song was specifically written about Bangor.[63]

Bangor, Pennsylvania

[edit]The United States town of Bangor in the Lehigh Valley region of eastern Pennsylvania draws its name from Bangor, Gwynedd. It was settled around 1760 by Robert M. Jones, an emigrant from Bangor, Gwynedd who went on to be influential in the development of the town's slate industry. Slate quarries still exist in the small Pennsylvania town, but only a few are still functioning. A life-sized statue of Jones, dedicated on 24 September 1914, remains in the town centre.[64] The influence of Bangor, Gwynedd is visible in the stone walls, square gardens, flowers, and greenery that mirror those of its Welsh namesake. Also like Bangor (Wales), Bangor (Pennsylvania) has piles of slate residue and shale reminiscent of the area.[65]

Notable people

[edit]

- William Ambrose (1813–1873), bardic name Emrys, poet and preacher.

- Brenda Chamberlain (1912–1971), a Welsh artist, poet and writer.

- John Edward Daniel (1902–1962), theologian, college lecturer and war-time chairman of Plaid Cymru.

- Richard Deacon (born 1949), abstract sculptor, winner of the Turner Prize.

- Matthew Dent (born 1981), graphic artist and designer of the redesigned 2008 British coinage.

- Duffy (born 1984), singer-songwriter. First Welsh woman to achieve No. 1 in the UK Singles Chart since 1983.

- Endaf Emlyn (born 1944), musician, film and TV director.

- Ren Gill (born 1990), musician.[citation needed]

- Mary Dilys Glynne (1895–1991), plant pathologist and mountaineer.

- George Guest (1924–2002), an organist and choral conductor.

- Owen Hurcum (born 1997), politician, former mayor of the city of Bangor.

- Dylan Jones-Evans (born 1966), professor and newspaper columnist

- Sian Lloyd (born 1968), Welsh TV news presenter, works for BBC News

- Angus McDermid (1920–1988), BBC News foreign correspondent.

- Owain Owain (1929–1993), nuclear scientist, novelist, short-story writer and poet.

- Harry Parry (1912–1956), jazz clarinetist and bandleader.[66]

- Ben Roberts (1950–2021), actor, played C.I. Derek Conway in the ITV series, The Bill.

- Sasha (born 1969), DJ and record producer.[67]

- Gwilym Simcock (born 1981), pianist and composer, often blurring jazz and classical music

- Charles Warren (1840–1927), Royal Engineer, archaeologist and Police Chief

- John Francon Williams (1854–1911), editor, journalist, geographer, historian, cartographer and inventor; born in Llanllechid and lived in Bangor as a child.

Sport

[edit]

- Errie Ball (1910–2014), golfer, played in first Masters Tournament in 1934.[68]

- Nicola Davies (born 1985), former football goalkeeper with 64 caps with Wales women

- Wayne Hennessey (born 1987), football goalkeeper with over 280 club caps and 108 for Wales.

- Owain Tudur Jones (born 1984), footballer with 258 club caps and 7 for Wales.

- Robin McBryde (born 1970), rugby union hooker with 37 caps for Wales

- Sheila Morrow (born 1947), President of Great Britain Hockey since 2017.

- Eddie Niedzwiecki (born 1959), football goalkeeper with 247 club caps.

- Pat Pocock (born 1946), former cricketer, played in 25 Test matches

- Rachel Taylor (born 1983), rugby union player with 43 caps for and captain of Wales women

- Alex Thomson (born 1974), record-breaking solo around-the-world sailor.

- Marc Lloyd Williams (born 1973), footballer, Welsh Premier League's top scorer, with 319 goals.

Twin town

[edit]Bangor is twinned with Soest in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany.

References

[edit]- ^ "Bangor Community". City Population. Retrieved 24 November 2024.

- ^ "Towns and cities, characteristics of built-up areas, England and Wales: Census 2021". Census 2021. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 8 August 2023.

- ^ "bangor". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d. Retrieved 16 January 2024.

- ^ "bangor". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 16 January 2024.

- ^ Wade-Evans, Arthur. Welsh Medieval Laws. Oxford Univ., 1909. Accessed 31 January 2013.

- ^ Myhill (web), Samantha Letters (content); Olwen (18 June 2003). "Gazetteer of Markets and Fairs to 1516: Wales". archives.history.ac.uk.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Bangor High Street Timeline". www.bangorcivicsociety.org.uk.

- ^ Historic Towns Survey of Gwynedd: Bangor (PDF). Bangor: Gwynedd Archaeological Trust. 2007. p. 9. Retrieved 24 November 2024.

- ^ "Bangor (33003)". Coflein. RCAHMW.

- ^ "Bangor – Gazetteers". Genuki.

- ^ "Life at the BBC". bbc.com.

The BBC is bombed – Hitler said that in war, words are actions. It is not surprising then that his bombers targeted Broadcasting House in London or that the BBC had contingency plans for just such an event. These involved evacuating whole departments out of London. So Music went to Bedford, and Drama and Variety were based in Bristol until that city too came under fire, and Variety was transferred to Bangor in North Wales.

- ^ Beckett, John (2005), City Status in the British Isles, 1830–2002, Routledge, p. 12, ISBN 978-0-7546-5067-6, archived from the original on 1 December 2017, retrieved 27 November 2017

- ^ Beckett, J. V. (2005). City status in the British Isles, 1830–2002. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 22. ISBN 9780754650676. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- ^ Beckett, John (5 July 2017). City Status in the British Isles, 1830–2002. Routledge. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-351-95125-8.

- ^ "Bangor (Gwynedd, Wales / Cymru, United Kingdom) – Population Statistics, Charts, Map, Location, Weather and Web Information". www.citypopulation.de. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ "Contact". Bangor City Council. Retrieved 24 November 2024.

- ^ "Penrhyn Hall". Coflein. Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales. Retrieved 24 November 2024.

- ^ "The City of Bangor Council Coat of Arms, Diocesan Registry, Bangor, Gwynedd, Wales". Waymarking. Retrieved 24 November 2024.

- ^ "First non-binary mayor 'of any city, anywhere' hailed an 'example to all' after winning election aged 22". PinkNews. 12 May 2021. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ^ "It's 9.01pm in Bangor. Do you know where your children are? (If not, they might be locked up)". The Independent. London. 19 June 2012. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ "Bangor Ancient Parish / Civil Parish". A Vision of Britain through Time. GB Historical GIS / University of Portsmouth. Retrieved 24 November 2024.

- ^ a b Jones, G. (1988). "Maenol Bangor: an ancient estate on the north-west fringe of Wales". Hommes et Terres du Nord. 1: 56–60. doi:10.3406/htn.1988.3051.

- ^ Report of the Commissioners appointed to inquire into the Municipal Corporations in England and Wales: Appendix 4. 1835. p. 2578. Retrieved 24 November 2024.

- ^ Parliamentary Boundaries Act. 1832. p. 372. Retrieved 24 November 2024.

- ^ "No. 21128". The London Gazette. 20 August 1850. p. 2277.

- ^ Peter Ellis Jones. "Bangor - Charter of incorporation" (PDF).

- ^ "The Charter of Incorporation of the City of Bangor". Bangor Civic Society. Retrieved 9 March 2022.

- ^ Langston, Brett. "Bangor Registration District". UK BMD. Retrieved 24 November 2024.

- ^ "Local Government Act 1972", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 1972 c. 70, retrieved 6 October 2022

- ^ "Local Government (Wales) Act 1994", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 1994 c. 19, retrieved 9 October 2022

- ^ "THE LONDON GAZETTE, 4TH APRIL 1974" (PDF).

The QUEEN has been pleased by Letters Patent under the Great Seal of the Realm, bearing date the 1st day of April 1974, to ordain that the Town of Bangor shall have the status of a City.

- ^ a b "Bangor (Gwynedd, Wales / Cymru, United Kingdom) - Population Statistics, Charts, Map, Location, Weather and Web Information". www.citypopulation.de. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ^ "Ministers outline the aims for Wales to become an anti-racist nation". North Wales Chronicle. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ^ Owen, Annie (4 July 2021). "The 'forgotten' members of North Wales' Muslim community 'left behind' by Welsh Government pilot". North Wales Live. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ^ "Timetables". Transport for Wales. May 2023. Retrieved 29 August 2023.

- ^ "Stops in Bangor". Bus Times. 2023. Retrieved 29 August 2023.

- ^ "Gwynedd Archaeological Trust – Ymddiriedolaeth Archaeolegol Gwynedd". www.heneb.co.uk. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ "About us". North Wales Wildlife Trust. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ Williams, Mike (23 February 2016). "Bangor's new Storiel centre saw 5,000 visitors before it even officially opened". North Wales Chronicle. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- ^ "Bryn Terfel: Pontio theatre named after opera star in Bangor". bbc.co.uk. 11 October 2013. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- ^ "Pontio centre opens its doors to the public in acrobatic 'Welcome Day'". bbc.co.uk. 29 November 2015. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

- ^ a b "Bangor Garth Pier, North Wales". The Heritage Trail. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ^ "Bangor Pier, Garth Road, Bangor". British Listed Buildings. Archived from the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ^ "Bangor Pier". National Piers Society. Archived from the original on 13 January 2012. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ^ "Cathedral Church of St Deiniol, Bangor". British Listed Buildings. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ^ "Theatr Gwynedd". Theatres Trust. Archived from the original on 18 June 2019. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ "The County". Theatres Trust. Archived from the original on 18 June 2019. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ "SCENE I. Bangor. The Archdeacon's house". Archived from the original on 4 May 2016. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- ^ "Plaza Cinema in Bangor, GB – Cinema Treasures". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- ^ "City Cinema in Bangor, GB – Cinema Treasures". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- ^ "OS and ONS release report on the geography of Britain's high streets". Ordnance Survey Blog. 6 June 2019.

...in Wales it is High Street in Bangor at 1265m

- ^ "Welsh speakers by electoral division, 2011 Census". Welsh Government. Archived from the original on 28 May 2015. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ^ Emery, Frank; White, Paul (1975). "Welsh-Speaking in Wales According to the 1971 Census". Area. 7 (1): 26–30. JSTOR 20000922.

- ^ a b Internet Memory Foundation. "ARCHIVED CONTENT UK Government Web Archive – The National Archives". Archived from the original on 2 October 2015. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ^ a b "Cyfrifiad: Niferoedd y siaradwyr Cymraeg wedi disgyn". Golwg360. 11 December 2012. Archived from the original on 9 May 2015. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ^ "Ystadegau am iaith disgyblion, Ionawr 2014 a 2015 – a Freedom of Information request to Welsh Government". WhatDoTheyKnow. 11 September 2015. Archived from the original on 26 November 2016. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- ^ "HISTPOP.ORG – Search > Results > Counties of Carnarvon and Anglesey, 1921 Page Page i". www.histpop.org. Archived from the original on 7 February 2018. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- ^ "HISTPOP.ORG – Search > Results > County of Anglesey and Caernarvon (Part I), 1931 Page Page xxii". www.histpop.org. Archived from the original on 7 February 2018. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- ^ "NHS beds by organisation and year, 2009-10 onwards". statswales.gov.wales. Retrieved 16 January 2023.

- ^ "Hospital Records: Details: Caernarvon and Anglesey General Hospital, Bangor". The National Archives. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- ^ "Bangor and the Beatles". Bangor University. Archived from the original on 11 December 2014. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- ^ "The Beatles in Bangor". BBC Wales. 2 September 2009. Archived from the original on 25 November 2015. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- ^ "Singing star's fond memories of Bangor". Daily Post. 19 April 2013. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ^ Around Bangor By Cindy LaPenna pg. 10

- ^ Around Bangor By Cindy LaPenna pg. 11

- ^ Davies, John; Jenkins, Nigel; Menna, Baines; Lynch, Peredur I., eds. (2008). The Welsh Academy Encyclopaedia of Wales. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. p. 651. ISBN 978-0-7083-1953-6.

- ^ Larkin, Colin (2000). The Virgin Encyclopedia of Nineties Music. London: Virgin. p. 340. ISBN 978-0-7535-0427-7.

- ^ "Ball, the Last Master Standing, celebrates 100th birthday". Professional Golfers' Association of America. 16 November 2010. Archived from the original on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

External links

[edit] Bangor, Wales travel guide from Wikivoyage

Bangor, Wales travel guide from Wikivoyage