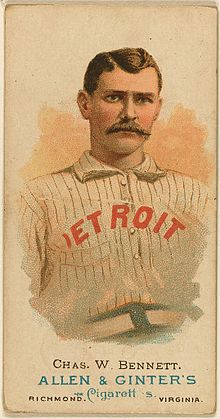

Charlie Bennett

| Charlie Bennett | |

|---|---|

| |

| Catcher | |

| Born: November 21, 1854 New Castle, Pennsylvania, U.S. | |

| Died: February 24, 1927 (aged 72) Detroit, Michigan, U.S. | |

Batted: Right Threw: Right | |

| MLB debut | |

| May 1, 1878, for the Milwaukee Grays | |

| Last MLB appearance | |

| September 30, 1893, for the Boston Beaneaters | |

| MLB statistics | |

| Batting average | .256 |

| Home runs | 55 |

| Runs batted in | 533 |

| Teams | |

Charles Wesley Bennett (November 21, 1854 – February 24, 1927) was an American professional baseball player from 1875 or 1876 through the 1893 season. He played 15 years in Major League Baseball, principally as a catcher, with the Milwaukee Grays (49 games, 1878), Worcester Ruby Legs (51 games, 1880), Detroit Wolverines (625 games, 1881–1888) and Boston Beaneaters (337 games, 1889–1893). He played on four pennant-winning teams, one in Detroit and three in Boston, and is one of only two players (the other being Ned Hanlon) to play with the Detroit Wolverines during all eight seasons of the club's existence.

Bennett compiled a .256 batting average and a .340 on-base percentage during his major league career with 549 runs scored, 203 doubles, 67 triples, 55 home runs and 533 runs batted in (RBIs). His greatest value, however, was as one of the greatest defensive players of his era. Between 1880 and 1891, he ranked among the National League leaders 10 times in Defensive Wins Above Replacement (Defensive WAR) at all positions and led the league's catchers seven times in fielding percentage and three times in double plays and putouts.[1]

Bennett's baseball career ended in January 1894 when he lost both legs in a train accident in Kansas. In 1896, Detroit's new baseball stadium was named Bennett Park in his honor. The Detroit Tigers played their home games at Bennett Park from 1896 through the 1911 season. Bennett has also been credited with inventing the first chest protector, an improvised cork-lined vest that he wore under his uniform.

Early years

[edit]Bennett was born in New Castle, Pennsylvania, in 1854.[1] His father, Silas Bennett (1815–1887), was a native of Connecticut. His mother, Catherine (Nichols) Bennett, was a native of Pennsylvania. Charlie was the eighth of their 11 children.[2][3]

Professional baseball player

[edit]Neshannock

[edit]Bennett began his career in organized baseball as the catcher for the Neshannock team in the Pennsylvania League.[4] Sources are in conflict as to how long Bennett played for Neshannock, one account indicating he was on the Neshannocks' "pay roll for two seasons",[5] and others stating that he played for the Neshannocks in 1874, 1875 and 1876.[6][7] Bennett was described while playing for the Neshannocks as a hard hitter who "nearly broke the directors of the club because of the number of balls knocked into the Shenango river."[7][8] While playing for Neshannock, Bennett was the catcher for Cal Hawk, one of the pitching stars of the early 1870s.[9]

Detroit Aetnas

[edit]At the end of the 1876 season, at age 22, Bennett signed with the Detroit Aetnas. The Aetnas were originally an amateur baseball team, but the club signed several professional players at the end of the 1876 season to aid in a rivalry with the Cass Club of Detroit. The professional players signed by the Aetnas included three members of the Neshannock team—Bennett, George Creamer and Ned Williamson.[8][10] Bennett's first appearance for the Aetnas was on September 21, 1876, against the Boston Red Stockings at the Woodward Avenue grounds in Detroit. Bennett played third base in the game and, in the first inning, hit a "hot one" that glanced off the pitcher and continued into center field for a triple that drove in a run.[11] The Aetnas' professional players, including Bennett, remained until the end of the season and were "stranded" in Detroit "without a dollar", until a "benefit was given and enough money realized to pay their way home."[10]

Milwaukee Grays

[edit]Some sources state that Bennett signed with the Philadelphia Athletics in 1877 and played in one game for that team.[12] He ultimately signed a contract to play in 1877 for the Milwaukee club at a salary of $150 per month.[5] During Bennett's first season with Milwaukee, the team was part of the League Alliance, which has been classified as a minor league.[13] The following year, the Milwaukee club was admitted to the National League and became the Milwaukee Grays. Bennett made his major league debut on May 1, 1878, and appeared in 49 games, 35 as a catcher and 20 in the outfield. He compiled a .245 batting average for the Grays with 16 runs scored and 12 RBIs.[1] His battery-mate, Sam Weaver lost 31 games that season.[14]

Worcester Ruby Legs

[edit]

In 1879, after the Milwaukee club disbanded,[4] Bennett joined the Worcester Ruby Legs, a team organized and managed by Frank Bancroft. The team played in the National Association, which has been rated as having been a minor league in 1879. Bennett began at Worcester as a backup catcher to Doc Bushong, but eventually replaced Bushong.[5] Bennett hit .328 in 42 games during the 1879 season.[13]

During the winter of 1879–1880, Bancroft took his team, including Bennett, on a baseball tour of Cuba and the Southern United States. Bennett stayed in New Orleans and played for local baseball teams there until the 1880 season began.[15]

In 1880, Worcester was admitted to the National League, replacing the Syracuse Stars, and attaining major league status.[6] That season, Bennett appeared in 51 games, 45 of them as the team's catcher.[1] Bennett caught for Lee Richmond, baseball's first left-handed pitching star.[5] Richmond compiled a 32–32 record in 1880,[16] and also pitched the first perfect game in major league history, with Bennett catching. Bennett had a .228 batting average with 20 runs scored and 18 RBIs during the 1880 season. Defensively, he ranked second among the National League's catchers with a .913 fielding percentage and fifth in putouts and range factor.[1]

Detroit Wolverines

[edit]At the end of the 1880 season, Bancroft, who had been Bennett's manager in Worcester, signed as the manager of a new Detroit baseball club that was admitted to play in the National League starting in 1881. Bancroft brought several Worcester players with him, including Bennett, George Wood, and Lon Knight.[6] Bennett played eight seasons with the Detroit Wolverines. He was one of only two players, the other being Ned Hanlon, to play for the Wolverines during every season that the franchise existed.

In his first season with Detroit, Bennett established himself as one of the best players in the National League. With a .301 batting average and a .478 slugging percentage,[1] Bennett's overall Wins Above Replacement (WAR) rating of 4.2 was the second highest among all of the league's position players, trailing only Cap Anson (5.8 WAR).[17] He also finished among the league leaders with seven home runs (2nd), 64 RBIs (2nd), .478 slugging percentage (4th), and 32 extra base hits (4th).[17] Bennett also excelled defensively in 1881, leading the league's catchers in putouts (418) and range factor (7.19), compiling the second highest Defensive WAR rating in the league, and setting a major league record for catchers with a .962 fielding percentage (.962). With his strong performance on both offense and defense, Bennett helped lead the Wolverines to a respectable 41–43 record in the first season of the franchise's existence.[18] According to baseball historian Peter Morris, Bennett took the first recorded "curtain call" in baseball during the 1881 season. After hitting a home run in May 1881, Bennett was "loudly applauded, and the crowd would not desist until he bowed in acknowledgment."[19]

In 1882, Bennett had another strong season, batting .301 and compiling a 4.1 WAR rating that ranked sixth in the league among position players. He also ranked among the league leaders with a .450 slugging percentage (6th), 10 triples (10th), and five home runs (4th). Defensively, he led the league's catchers with 446 putouts and a 7.94 range factor.[1] Bennett was the Wolverines' dominant offensive player, and helped the team to its first winning record at 42–41.[20]

In 1883, Bennett hit for a career high .305 batting average, and his 4.9 WAR rating was the third highest among the National League's position players, trailing only Dan Brouthers and Jack Farrell.[21] Bennett's defensive performance as dominant as his offense, with a 1.8 Defensive WAR rating that was the highest among catchers and the third highest among all players in the league.[21] He also led the league's catchers with 11 double plays turned and a .944 fielding percentage.[1] As good as Bennett was in 1883, the Wolverines team was not good, dropping to seventh place with a 40–58 record.[22]

In 1884, matters got worse for the Wolverines, as they finished in last place with a 28–84 record.[23] Bennett's batting average fell to .264, but his on-base percentage remained high at .334, and his WAR rating remained strong at 4.1.[1] Bennett later recalled the toll of multiple losing seasons in Detroit: "During the next four years [1882–1885] I wished many times I was out of Detroit, or, rather, out of that team. It was awful. I thought sometimes we were lucky to finish last. Once we lost twenty-five straight games. Every week I caught a new pitcher."[24]

In June 1885, the Wolverines added another slugger in Sam Thompson, and the team improved incrementally to sixth place with a 41–67 record.[25] Bennett compiled a 4.5 WAR rating for the season, the second highest of his career and fifth highest among the league's position players. He was also among the league leaders with 42 extra base hits (4th), 47 bases on balls (5th), a .456 slugging percentage (6th), 24 doubles (6th), a .356 on-base percentage (7th), and 64 RBIs (10th).[1] Defensively, he led the league's catchers with a 7.00 range factor and ranked second in double plays (10), fielding percentage (.919) and putouts (347).[1]

In 1886, the Wolverines added several star players and improved substantially, finishing in second place with an 85–38 record.[26] Bennett put in another solid year for the Wolverines with a .371 on-base percentage and a 3.9 WAR rating. He also compiled perhaps his best defensive season with a 2.0 Defensive WAR rating that was the highest among all players in the National League. He also led the league's catchers in fielding percentage (.955), double plays (13), and putouts (425), and ranked second in range factor (7.38).[1]

The 1887 season was the pinnacle in the history of the Detroit Wolverines. The team won the National League pennant with a 79–45 record and then defeated the St. Louis Browns in the 1887 World Series.[27] Bennett's WAR rating of 1.7 was the lowest during his time in Detroit, but still a respectable showing. Even though he was limited by injury to 46 games during the regular season, Bennett still finished with the sixth highest Defensive WAR rating among all players in the league and compiled a .363 on-base percentage.[1] In his only World Series, Bennett had nine RBIs, 11 hits, and a triple, stole five bases, and scored six runs.[1]

During the 1887 season, an excursion of fans from Bennett's hometown in Pennsylvania traveled to watch Bennett play in Detroit who enjoyed watching him receive a wheel barrow loaded with 500 silver dollars when the Wolverines returned to Detroit to celebrate their 1887 world championship victory. Bennett then wheeled the barrow around the field "to the delight of 5000 people."[12]

During the 1888 season, Bennett rebounded with one of the best seasons of his career. His overall 4.2 WAR rating was the third highest of Bennett's career, and his 2.2 Defensive WAR rating was the highest of his career and the second highest in the National League. Despite being the eighth oldest player in the league, he broke his own major league record with a .966 fielding percentage.[1] The Wolverines as a whole finished in fifth place with a 68–63 record.[28] With high salaries owed to the team's star players, and gate receipts declining markedly, the team folded in October 1888 with the players being sold to other teams. On October 16, 1888, the Wolverines sold Bennett, Dan Brouthers, Charlie Ganzel, Hardy Richardson and Deacon White to the Boston Beaneaters for a price estimated at $30,000.[1]

Chest protector

[edit]Bennett has been credited with inventing the first chest protector worn by catchers.[29] According to Bennett, his wife worried about his safety as "a target for the speed merchants" and saw a need for a form of body armor to protect her husband from broken ribs. Bennett and his wife designed a homemade shield by sewing thick strips of cork between layers of "heavy bedticking material". Out of a concern for spectators "roasting him for being chicken-hearted", he wore the device under his shirt.[30]

Durability as a catcher

[edit]During Bennett's era, catchers lacked the protective equipment present in 20th-century baseball. It was not until 1888 that specialized catcher's mitts began to be used on the non-throwing hand.[31] As a result, catchers' hands, fingers, legs, and bodies took a beating in Bennett's time. For this reason, catchers in the era were not every-day players, needing time to recuperate after catching a game. When Bennett began his major league career, the major league record for games caught in a season was 63 games.[32]

Most catchers of the 1870s and 1880s minimized wear and tear on their hands by playing some games at other positions. For example, the three "catchers" from the era who have been inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame each played less than half of their games as a catcher: (1) Buck Ewing, often cited as the greatest catcher of the 19th century, played only 636 of his 1,345 games (47%) as a catcher;[33] (2) King Kelly played only 583 of his 1,455 games (40%) at catcher;[34] and (3) Deacon White eventually moved to third base as his regular position, finishing his career with only 458 of 1,622 games (28%) as a catcher.[35] Bennett, on the other hand, played 954 of his 1,084 games (88%) at the catcher position.[1][36]

Bennett's durability came not from avoiding injuries, but from playing through them. When he broke another finger during the 1887 World Series, The New York Times reported:

It did not seem anything unusual to Bennett or his fingers. ... When he held up that battered right hand, with its fingers swollen and spread like a boxing glove, with rags tied around three of them, and a general appearance of having been run over by a freight-car about the entire hand, it did not seem as though there were room to split it in any new place.[37]

Accounts of Bennett's mangled or gnarled hands and fingers are common. In his book, Catcher: The Evolution of an American Folk Hero, Peter Morris cited one such account:

Bennett 'declared that only a sissy would use a padded glove with the fingers and thumb cut off. During one of the games in which he figured a foul ball split the left thumb of Bennett's hand from the tip right down to the palm. The flesh was laid open right to the bone. A doctor who examined it immediately told Bennett that it would be necessary for him to quit the game until such time as the thumb healed sufficiently. The physician pointed out ... that blood poisoning might set in which would cause him the loss not only of the thumb but perhaps a hand or an arm. But despite all the doctor's caution Bennett remained in the game catching day after day with his horribly mangled finger. He kept a bottle of antiseptic and a wad of cotton batting on the bench and between innings would devote his time to washing out the wound.'[38]

Another account arises out of the 1889 pennant race. That year, Bennett played for the Boston Beaneaters in a close pennant race with the New York Giants. Bennett's hands had taken a beating while catching for John Clarkson, who won 49 games and pitched five games a week during the season. On the last day of the season, Boston had to win, and New York had to lose for Boston to finish in first place. By the sixth inning, second baseman Hardy Richardson told the manager, Jim Hart, that the ball was coming to him in a bloody state due to the condition of Bennett's hands. Bennett did not want to come out of the game, but Hart removed him over Bennett's protest, and Bennett "had to keep his hands in plasters for two weeks."[39]

Despite the physical battering and breaking every finger on both hands, Bennett was able to continue catching for 20 years (1874–1893).[1][13] His total of 954 major league games at catcher stood as the record until 1897.[32]

Boston Beaneaters

[edit]

After a brief dispute with the Boston management with respect to his salary, Bennett signed a contract with the club In January 1889.[7] That year, Bennett appeared in 82 games, all at catcher. His batting average dropped to .231, his lowest tally since he was a part-time player in 1880. However, he continued to show his value defensively. Despite being the sixth oldest player in the National League, Bennett finished fifth among all players at all positions with a Defensive WAR of 1.4. He also led the league's catchers with a .955 fielding percentage, ranked second among the league's catchers with 419 putouts and third with nine double plays turned.[1] With Bennett's assistance, Boston pitcher John Clarkson compiled a 49–19 record, and the Beaneaters finished second in the league with an 83–45 record.[40]

In 1890, Bennett remained with the Beaneaters even though he had in 1886 joined the Brotherhood of Professional Base-Ball Players, the union that represented the players and organized the Players' League in response to unfair treatment by team owners. As a member of the Brotherhood, his refusal to play in the Players' League was criticized by many of his fellow Brotherhood members. Hardy Richardson, a Brotherhood representative and former teammate of Bennett, stated that Bennett offered to sign with the Brotherhood only if he was given a three-year contract guaranteed by two responsible men.[41] Some reports indicated that former Detroit manager Robert Leadley was paid $1,000 to convince Bennett to remain with the Beaneaters and that Bennett was himself paid a substantial signing bonus.[12][41][42][43] Bennett later described his ambivalence about the Players' League: "I was a Brotherhood man from the first. Mrs. Bennett was strongly opposed to my going into it and before the season opened I told my friends that I could not join them, so I remained with the Boston Club. When I went into the Brotherhood it was a protective order and I had no idea that they intended organizing an association of their own."[44]

Bennett became the catcher for Baseball Hall of Fame pitcher, Kid Nichols, in 1890, as Nichols compiled a 27–19 record while Clarkson went 26–18. The team finished in fifth place with a 76–57 record.[45] Offensively, Bennett's production continued to decline, as he finished the 1890 season with a .214 batting average. Though he had only 60 hits, he also drew 72 bases on balls, boosting his on-base percentage to .377. Already the third oldest player in the league, Bennett nevertheless also continued to rank among the best defensive catchers. He led the league's catchers with a .959 fielding percentage and ranked fourth in putouts and double plays and fifth in assists and runners caught stealing.[1]

In 1891, Bennett appeared in 75 games, all as a catcher, for a Boston team that won the National League pennant with an 87–51 record. The team had two 30-game winners, as John Clarkson won 33 and Kid Nichols won 30.[46] Bennett's batting average remained low at .215, but his .332 on-base percentage was significantly higher. Moreover, he led the National League in fielding percentage by a catcher for the seventh time in his career. He also led the league with 10 double plays turned by a catcher.[1]

In 1892, King Kelly took over as the Beaneaters' number one catcher. In a backup role, Bennett, at age 37, appeared in 35 games as Boston's catcher. The team continued to play well, winning its second consecutive National League pennant with a 102–48 record.[47]

In 1893, Bennett returned to his role as the team's number one catcher, appearing in 60 games at the position. In that role, he helped Boston win its third consecutive National League pennant with an 86–43 record.[48] Bennett compiled a .209 batting average and .352 on-base percentage and appeared in what proved to be his final baseball game on September 30, 1893.[1]

Train accident

[edit]

While playing for Boston, Bennett returned each year to his home in Detroit for the off-season, and also traveled with his dog to Williamsburg, Kansas, for extended hunting trips. In 1894, Bennett was joined on his annual hunting trip by pitcher John Clarkson. On January 10, 1894, Bennett's legs were crushed by a Santa Fe Railroad passenger train in Wellsville, Kansas, while traveling from Kansas City to Williamsburg.[12]

Bennett stepped off the train to talk to an old friend who lived in Kansas and whom Bennett had arranged to greet when the train stopped at Wellsville. It was raining, and the platform was wet. When the train started moving, Bennett "swung around to catch the railing", but his foot slipped, and his left foot went over the rail. Bennett pushed his right leg against the rail to push himself back, but it also slipped and went over the track. The train's wheels ran over his left foot and right leg at the knee.[24][44][49]

That evening, doctors at the North Ottawa Hospital in Ottawa, Kansas, amputated Bennett's left leg just above the ankle and his right leg just above the knee.[42] In June 1894, he was fitted with artificial limbs, but his baseball career was over.[44] In August 1894, a benefit to raise money for Bennett was held at Boston's South End Grounds; the event included a baseball game between the Boston team and a team of collegiate players as well as foot races and other attractions.[50] The boxing champion Gentleman Jim Corbett attended and briefly played in left field with the Boston team. The benefit was attended by nearly 9,000 people and raised $6,000 for Bennett. Bennett walked to home plate during the event, aided by crutches and artificial limbs, and bowed to the crowd "until the grounds fairly shook with cheers."[51]

Catching records and legacy

[edit]During his 15 years in the major leagues, Bennett set numerous fielding records. Several of those records are set forth below.

- Fielding percentage. In 1882, Bennett set a major league record with a .962 fielding percentage as a catcher. He broke his own major league record in 1888 with a .966 fielding percentage. Bennett's career fielding percentage of .942 stood until 1896 as the major league career record. Bennett also led all major league catchers in fielding percentage six times; no other catcher has accomplished this feat more than four times.[52]

- Putouts. In 1886, Bennett set a major league, single-season record with 445 putouts by a catcher. His career total of 5,123 putouts was also a major league record that stood until 1901.[53]

- Double plays. In 1887, Bennett broke the career record for most double plays turned as a catcher. His final career total of 114 double plays was the major league record until 1900.[54]

- Games played. Bennett's career total of 954 games at catcher stood as the major league record until 1897.[32]

Sports writer Tim Murnane in 1894 declared Bennett "unquestionably the greatest back stop the game ever produced, taking his throwing and batting into consideration ... Year after year Bennett led the catchers of the League and country until it seemed impossible to get a player to head him off. It made no difference to him who pitched the ball, he was there to catch it, and always with big hands. Who can remember Bennett dropping a pitched ball? Passed balls were a lost art when this man was behind the stick, and he was the ideal back stop. [Kid] Nichols always insisted on having him do his catching, saying that Bennett knew every batsman's weak points, and made easy work for the pitcher."[42]

Pitcher Lee Richmond, whose perfect game Bennett caught in 1880, later stated that, among the catchers he had worked with, "my favorite was Charley Bennett, the best backstop that ever lived in the world. He went after everything, he knew no fear, he kept his pitcher from going into the air."[55]

In The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract, sports historian Bill James wrote that Bennett was perhaps the best defensive catcher of the era. In comparing Bennett to Buck Ewing, James noted: "Buck Ewing was supposedly a brilliant catcher, but Bennett caught 50% more innings than Ewing, with a lot fewer mistakes: per 1000 defensive innings, Ewing was charged with 59 errors and 66 passed balls, while Bennett was charged with 46 errors and 43 passed balls."[56] Although James ranked Ewing ahead of Bennett as an overall player, he chose Bennett as the catcher on his Gold Glove Team for the 1880s.[57] On the offensive side, Ewing compiled a .303 career batting average, 47 points higher than Bennett. However, with Bennett's talent for drawing walks, Ewing's career on-base percentage (.351) was only 11 points higher than Bennett (.340).[1][33]

Family and later years

[edit]

In 1882, Bennett was married to his wife, Alice, a Vermont native. They met while Bennett was playing for Worcester. They had no children,[12] and lived for more than 20 years at 67 Alexandria Street in Detroit,[58][59][60][61] and later at 1313 Delaware Avenue in Detroit.[62]

After his injury, Bennett operated a cigar store in Detroit.[29] When Bennett first announced plans to open a cigar store, shortly after losing his legs, one woman wrote to him and said, "If Charley Bennett opens a cigar store in Detroit, all the ladies will commence smoking."[24]

Bennett later took lessons in china painting and became quite proficient at the decorative art, first as a hobby and then as a supplemental source of income.[29][58][63] One writer wrote that the art of china painting was "the last thing one would expect in the world from a man whose hands have been battered out of shape and whose every finger has been broken."[58] The Sporting News wrote: "It was with characteristic patience that Bennett trained his distorted fingers in the delicate art of china painting."[29]

When a new ballpark was opened in Detroit in 1896, it was named Bennett Park in his honor. Bennett caught the first pitch at Bennett Park in 1896. It became a Detroit tradition for Bennett to catch the first pitch in Detroit, an honor that Bennett continued for every home opener through 1926.

In November 1926, Bennett underwent surgery at Grace Hospital in Detroit to remove "a superorbital abscess of the face."[62] He had been ill for several months before the surgery and never fully recovered afterward, as the poison from the abscess reportedly spread through Bennett's system. Bennett died in February 1927 at age 72 at his home in Detroit. He was buried at Woodmere Cemetery in Detroit.[1][29]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x "Charlie Bennett Statistics and History". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved July 9, 2014.

- ^ 1870 U.S. Census entry for Silas and Catherine Bennett residing in New Castle, Penn. Son Charles, age 14, born in Pennsylvania. Source Citation: Year: 1870; Census Place: New Castle Ward 1, Lawrence, Pennsylvania; Roll: M593_1360; Page: 102B; Image: 208; Family History Library Film: 552859. Ancestry.com. 1870 United States Federal Census [database on-line].

- ^ Charles Wesley Bennett profile on Ancestry.com. Birth 21 Nov 1854 in New Castle, Lawrence, Pennsylvania, USA. Death 24 Feb 1927 in Detroit, Wayne, Michigan, USA. Parents Silas Bennett (1815–1887) and Katherine Nichols (1815–1882).

- ^ a b "Poor Charley Bennett: The Afflicted Catcher Recites His Baseball Career; Telling of the Turbulent Times in Detroit in 1881". Detroit Free Press. June 23, 1894. p. 4. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved July 9, 2014.

- ^ a b c d McLean Kennedy (March 30, 1913). "Greatest Backstop of Them All Was The Detroit Boy, Charlie Bennett: Records Show No Catcher Superior to Famous Catcher of the 1887 World's Diamond Champions; Was Wonder in All Departments of Game – Cut Off in His Prime by Railroad Accident". Detroit Free Press. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved July 9, 2014.

- ^ a b c John H. Gruber (November 30, 1913). "Players of Other Days: Charley Bennett". Detroit Free Press. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved July 9, 2014.

- ^ a b c "Bennett Signed: Boston Gets a Famous Backstop; His Record While in the League". Boston Daily Globe. January 22, 1889. p. 5.

- ^ a b "A Nursery: A Club From Which Many Now Famous Players Graduated" (PDF). The Sporting Life. February 17, 1886. p. 1.

- ^ "A Veteran Dead: Cal Hawk, a Noted Player of the 70s, Called Out by the Great Umpire" (PDF). The Sporting Life. December 30, 1899. p. 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 14, 2014. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

- ^ a b "Record of the Aetnas: The Four Years' Career of the Club Was a Brilliant One". Detroit Free Press. February 24, 1889. p. 7. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved July 9, 2014.

- ^ "Base Ball: The Aetnas Beaten in Fine Style by the Bostons; The Score 14 to 3 in Favor of the Latter". Detroit Free Press. September 22, 1876. p. 1. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved July 9, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e T.H. Murnane (January 12, 1894). "Poor Bennett: Both of His Legs Cut Off at Wellsville, Kan.; Close of a Brilliant Career on the Baseball Field; He Led League Catchers Many Years; Sorrow of All Members of Champion Bostons; Will Live if Blood Poisoning Does Not Set In". Boston Daily Globe. p. 8.

- ^ a b c "Charlie Bennett Minor League Statistics". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved July 9, 2014.

- ^ "1878 Milwaukee Grays". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved July 9, 2014.

- ^ "Bennett Once Ranked AS King of Backstops". Boston Daily Globe. February 25, 1927. p. 26. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved July 9, 2014.

- ^ "Lee Richmond Statistics". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved July 9, 2014.

- ^ a b "1881 National League Batting Leaders". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

- ^ "1881 Detroit Wolverines". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

- ^ Peter Morris (2006). A Game of Inches: The Stories Behind the Innovations That Shaped Baseball: The Game on the Field. Ivan R. Dee. p. 414. ISBN 1566639549.

- ^ "1882 Detroit Wolverines". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

- ^ a b "1883 National League Batting Leaders". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

- ^ "1883 Detroit Wolverines". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

- ^ "1884 Detroit Wolverines". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

- ^ a b c "Poor Charley Bennett: The Afflicted Catcher Recites His Baseball Creer". Detroit Free Press. June 23, 1894. p. 4.

- ^ "1885 Detroit Wolverines". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

- ^ "1886 Detroit Wolverines". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

- ^ "1887 Detroit Wolverines". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

- ^ "1888 Detroit Wolverines". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Sam Greene (March 3, 1927). "Moriarty Sharpens His Managerial Eye: Detroit Loses Pioneer in Bennett's Death". The Sporting News. p. 1.

- ^ Maclean Kennedy (August 2, 1914). "Charlie Bennett, Former Detroit Catcher, Inventor of Chest Pad: Old-Time Star and Mrs. Bennett Made First One Out of Cork Sewed Between Bed-Ticking Strips". Detroit Free Press. p. 19.

- ^ Morris, Peter (2010). Catcher: How the Man Behind the Plate Became an American Folk Hero. Government Institutes. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-56663-870-8.

- ^ a b c "Progressive Leaders & Records for Def. Games as C". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved July 9, 2014.

- ^ a b "Buck Ewing Statistics and History". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

- ^ "King Kelly". Sports Reference LLC.

- ^ "Deacon White Statistics and History". Sports Reference LLC.

- ^ Others in Bennett's era who showed extraordinary durability, playing the vast majority of their games at the catcher position, include: Pop Snyder, 877 of 948 games (92.5%); Silver Flint, 743 of 817 games (91%); and Doc Bushong, 668 of 679 games (98.3%).

- ^ Richard Bak (1998). A Place for Summer: A Narrative History of Tiger Stadium. Wayne State University Press. p. 34.

- ^ Peter Morris (2009). Catcher: The Evolution of an American Folk Hero. Government Institutes. pp. 208–209. ISBN 978-1615780037.

- ^ "A Story of Charley Bennett". Detroit Free Press. January 23, 1898. p. 6.

- ^ "1889 Boston Beaneaters". baseball-reference.com.

- ^ a b "Foxy Charley Bennett: Director Hart Returns Unsuccessful; League Offers a $2500 Bonus and $1000 Blood Money". February 11, 1890. p. 5.

- ^ a b c "A Tragic Close to a Brilliant and Long Career on the Diamond: Details of the Horrible Accident Which Cut Off Bennett's Legs and Livelihood – A Tribute to the Suffering Player – Sketch of His Career" (PDF). The Sporting Life. January 20, 1894. p. 3.

- ^ "Charles W. Bennett: That Name is on a League Contract; Leadley Secures the Star for the Triumvirs". Boston Daily Globe. February 12, 1890.

- ^ a b c "Maimed Bennett: Interesting News About the Great and Popular Ex-Catcher; Quite Recovered From the Dreadful Accident Which Deprived Him of His Legs Cheerful and Hopeful For the Future" (PDF). The Sporting Life. June 2, 1894. p. 5.

- ^ "1890 Boston Beaneaters". baseball-reference.com.

- ^ "1891 Boston Beaneaters". baseball-reference.com.

- ^ "1892 Boston Beaneaters". baseball-reference.com.

- ^ "1893 Boston Beaneaters". baseball-reference.com.

- ^ "Bennett's Recovery Assured: Boston's Great Catcher is Gaining Much Faster Than Was Expected". Boston Daily Globe. January 19, 1894. p. 2.

- ^ "Charley Bennett's Benefit: It Will be a 'Corker' -- Exercises at the Ball Grounds – Charlie Arrives – Subscription Fund". Boston Daily Globe. August 26, 1894. p. 4.

- ^ "Nearly $6000: Benefit to Bennett Was a Grand Success; Catcher Bowed to 9000 Friends; Walked Out to Home Plate to Do It; Champion Corbett in the Left Field". Boston Daily Globe. August 28, 1894. p. 1.

- ^ "Progressive Leaders & Records for Fielding % as C". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved July 9, 2014.(Gabby Hartnett, Buddy Rosar and Sherm Lollar each led the majors four times, and Pop Snyder, Chief Zimmer, Ray Schalk and Brad Ausmus each led the majors three times.)

- ^ "Progressive Leaders & Records for Putouts as C". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved July 9, 2014.

- ^ "Progressive Leaders & Records for Double Plays Turned as C". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved July 9, 2014.

- ^ Elmer Bates (March 19, 1910). "Improved Game: J. Lee Richmond, Once a Great Pitcher, Is One of the Few Veterans Who Concedes Advance Base Ball". The Sporting Life. p. 12.

- ^ Bill James (2001). The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract. Free Press. pp. 402–403. ISBN 9780743227223.

- ^ Bill James, New Abstract, p. 42.

- ^ a b c "Peerless Old Catcher Now Paints China". The Spokane Press. January 24, 1908. p. 3.

- ^ 1900 U.S. Census entry for Charles W. Bennett (born Nov 1854 in Pennsylvania) and Alice Bennett (born Jan 1855 in Vermont). Source Citation: Year: 1900; Census Place: Detroit Ward 1, Wayne, Michigan; Roll: 747; Page: 7A; Enumeration District: 0007; FHL microfilm: 1240747. Ancestry.com. 1900 United States Federal Census [database on-line].

- ^ 1910 U.S. Census entry for Charles W. Bennett (age 55, born in Pennsylvania) and Alice Bennett (age 55, born in Vermont). Source Citation: Year: 1910; Census Place: Detroit Ward 1, Wayne, Michigan; Roll: T624_679; Page: 9B; Enumeration District: 0013; FHL microfilm: 1374692. Ancestry.com. 1910 United States Federal Census [database on-line].

- ^ 1920 U.S. Census entry for Charles W. Bennett (age 66, born in Pennsylvania) and Alice Bennett (age 66, born in Vermont). Source Citation: Year: 1920; Census Place: Detroit Ward 1, Wayne, Michigan; Roll: T625_803; Page: 13B; Enumeration District: 28; Image: 463. Ancestry.com. 1920 United States Federal Census [database on-line].

- ^ a b "Charley Bennett In Critical State". Boston Daily Globe. November 12, 1926. p. A27.

- ^ "Personal" (PDF). The Sporting Life. May 4, 1895. p. 9.

External links

[edit]- 1854 births

- 1927 deaths

- 19th-century baseball players

- 19th-century American sportsmen

- Major League Baseball catchers

- Milwaukee Grays players

- Worcester Worcesters players

- Detroit Wolverines players

- Boston Beaneaters players

- Baseball players from New Castle, Pennsylvania

- American amputees

- Milwaukee (minor league baseball) players

- Worcester Grays players

- Sportspeople with limb difference